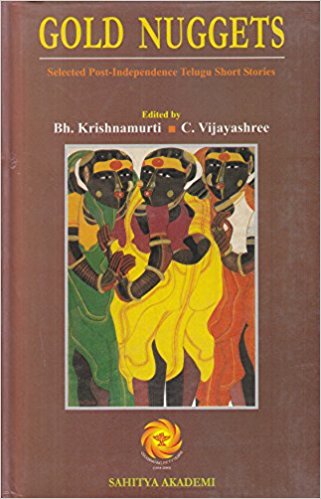

It appears that the editors of this anthology of English translation—Bh. Krsihnamurti, a linguistics man and former Vice-Chancellor of the University of Hyderabad, and C. Vijayashree, Professor of English at Osmania University—did not have much of a choice. They have translated a Telugu anthology put together by Vakati Panduranga Rao and Vedagiri Rambabu after a three-day workshop in 1997. This was published in 2001. Krishnamurti and Vijayashree have presented thirty of the original sixty published in the Telugu collection. It is to be taken that the English editors agreed with the choice made by the Telugu editors. Of course, the final rap and commendation for the anthology in this English version squarely belong to Krishna-murti and Vijayashree. This might appear to be a trivial issue but it assumes importance after the Penguin edition of Telugu short stories edited by Ranga Rao, which was focused and sharp, and there was a critical awareness of the translation process as well. Those qualities which marked the Penguin edition are not to be found in this one as a general principle. It is not that we are looking for a manifesto of translation.

December 2006, volume 30, No 12