Thanks to the excesses following 9/11 (racial profiling, waterboarding, rendition to other countries, etc.), counterterrorism has been a subject of much public scrutiny in the US. The recent disclosure of the Senate Intelligence Committee’s reports on the CIA torture programme is a case in point. The elaborate documentation sharply divided the country on the so-called ‘enhanced interrogation techniques’ and their effectiveness in thwarting terror plots or tracing masterminds like Osama Bin Laden. Such commotion in the US is all the more remarkable given that most of the victims of those human rights violations were nationals of other countries. Yet, it triggered off a campaign for a law to ensure that the US never again tortures.

Human Rights At the Altar of Security Expediency

Manoj Mitta

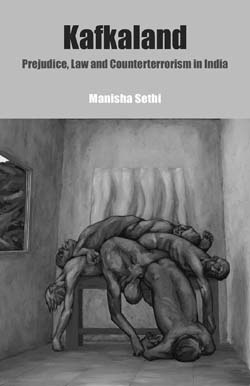

KAFKALAND: PREJUDICE, LAW AND COUNTERTERRORISM IN INDIA by Manisha Sethi Three Essays Collective, Gurgaon, 2015, 216 pp., 350

February 2015, volume 39, No 2