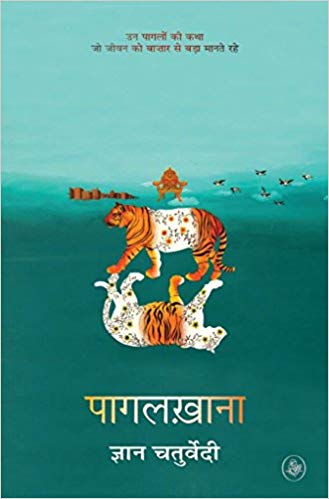

Padma Shri Dr. Gyan Chaturvedi (b. 1952), a noted cardiologist by training and a veteran Hindi satirist, explores the ravages of a world ruled by market culture in his fifth novel Pagalkhana. The novel employs the genre of satirical fantasy and an experimental narrative structure replete with interweaving stories, unnamed character types, and fragments, constructed with an economy of words, images and themes. His previous novels, Narak Yatra (based on the Indian medical system and teaching/training thereof), Baramasi, Marichika, and Hum Na Marab have established his niche in the annals of Hindi literature besides famous satirists like Harishankar Parsai, Sharad Joshi, Shrilal Shukla and the like. Pagalkhana is hardly a cautionary tale holding a window to a future completely overrun, owned and dictated by market forces, where time, personal freedom, dreams, memory, and all rational thoughts per se are systematically sucked out and annihilated, laid down to furthering the nefarious interests of the market.

These times can either be the signs of a golden era, a panacea for all ‘problems’ hindering the ‘progress’ of the human race, or, the epitome of a refashioned Kurtzian ‘Horror’ (Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness) which seeks to subsume ‘life’ as we have known it, of all things innocent, beautiful, and delicate, relinquishing all logic, rationality, and above all, control at the feet of the market forces driven by data, numbers, graphs and cold, stoic analysis. It is the latter that Chaturvedi expertly portrays in the 271 pages of Pagalkhana, where the lines between sanity and insanity seem to be blurred beyond easy recognition.

‘Bazarvaad’, the term Chaturvedi uses effortlessly throughout the novel, has no simple equivalents in English: it can be best understood as a market culture driven by ruthless capitalist and corporate interests, number-driven economic indices, consumerism of the worst order, and the vagaries of evolving globalized tendencies. The novel is prefaced with a long and detailed introduction where Chaturvedi candidly offers several crucial insights into his craft, the actual process of writing the novel, and the theme being explored. He claims to be following the tradition of Shrilal Shukla in investigating why a writer continues to write despite the ‘stressful, difficult and the somewhat long period of isolation’ (p.7) that the writer experiences in the process. Chaturvedi reveals that he worked on six drafts in all for Pagalkhana in a span of two years where the story consumed all his creative energies. He admits that writing this novel has been a unique experience for him, by far the most ‘difficult, challenging, tiring, isolating and forcing him to spend two years in the scariest world (as if in constant darkness)’ than any of his previous works: the topic was difficult, the genre of fantasy hard to rein in, and the necessity to escape flat reportage was looming large.