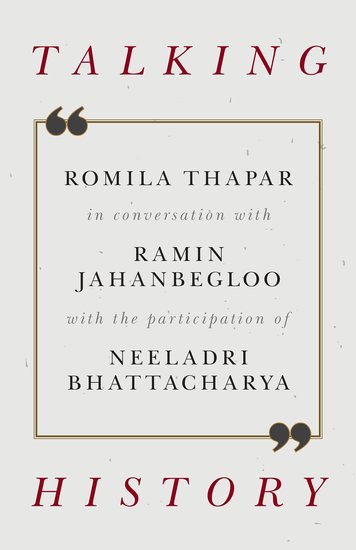

Ramin Jahanbegloo has had an enviably productive year, and seen another new title out since the release of Talking History. It comes as no surprise then, to open this book and discover it is the eighth in a series, each one a collection of interviews conducted by him. Figures as diverse as Raj Rewal and Vandana Shiva, Richard Sorabji and Sudhir Kakar, get a volume each to report on the state of play in their respective fields: architecture, environmentalism, philosophy, psychoanalysis—to cite a sample of the range. Isaiah Berlin, whose conversational skills Jahanbegloo likens to Romila Thapar’s, has been a decisive influence in his writing life. A book of conversations with Berlin was an early landmark of his career, and he is presently engaged on a recognizably Berlin-like project: putting faces and life histories to ideas that are shaping the contemporary understanding of India. If Romila Thapar is an obvious choice to represent the field of Indian history, she is also in another sense an unorthodox one. Since completing her PhD thesis at London University in 1958, later published as Ashoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, her writings—with their variety of form, theme and treatment, their address to a broad audience and steady rate of appearance—have given her a public profile that academics in India rarely achieve. Alongside this stands her reputation as a teacher, a founding member of the Jawaharlal Nehru University in 1970, and recipient of numerous international honours. She is emphatically a public figure for the hate she has drawn from the Hindu Right, but also one about whom not a great deal is generally known. The conversations in Talking History are a departure from this reserve. They touch on her childhood, family and schooling, and go into the sort of personal details that it may not have occurred to her, unprompted, to share. Thapar’s fame also diverts attention from her rather unusual position in the community of historians. A catholic figure in the midst of Marxians, with a Left-liberal ambivalence on the whole about research based on identitarian standpoints (even the feminist one), and definitely cool towards postmodernism—she has ploughed her own furrow; it is nonetheless easy to lose sight of the minority position she has occupied in the academy. The only label she accepts with ease is that of a Nehruvian.

January 2018, volume 42, No 1