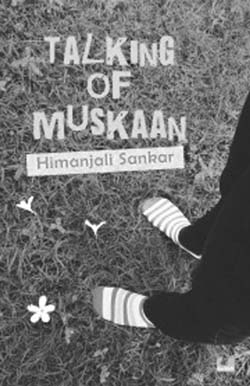

I’d already heard many good things about Himanjali Sankar’s young adult novel Talking of Muskaan, so I was really looking forward to reading the book. And I was far from disappointed. This is a bold novel in more ways than one. It is also one of the few Indian books for young adults I’ve read that isn’t imitative, has protagonists who come across as real with all the vulnerabilities and insecurities of their youth, and addresses growing up issues with a lightness of touch that doesn’t take away from the seriousness of the story. Given the current political climate in the country, Duckbill deserve applause for bringing out a book like this which talks about Section 377 without beating around the bush.

February 2015, volume 39, No 2