Cultural contacts between India and Southeast Asia were effectively broken with the coming of colonialism to Asia. British, French and Dutch colonial ambitions divided up Southeast Asia and the administration of their areas was kept entirely separate. But the realization that there had been close contact earlier between South Asia and Southeast Asia dates to the nineteenth century when the sites of old kingdoms were excavated and their history reconstructed. The remains of temples, sculpture, inscriptions and objects from the past, elicited much interest. Similarities with monuments and objects in India became the evidence for positing links.

Architectural remains were impressively large, sometimes larger than what were regarded as their proto-types in India and the sculpture had a distinctive style even where Indian counterparts were recognizable. Inevitably these discoveries triggered off many debates largely among European and Indian scholars on the exact nature of the contacts between South and Southeast Asia.

The basic questions related to the reason such contacts took place initially, how and why they were developed and what was the channel through which they were established, and when. Some scholars spoke about tolerance and peacefulness characterizing the contacts, others referred to the Southeast Asian kingdoms as Hindu colonies, but not as a result of conquest. The latter seems not to have been the agency through which Indian cultural symbols were either imposed or appropriated.

The theory that is now more widely discussed is that the contacts came about because of trade between the two areas and that there might have been settlements of traders that introduced Indian culture to the region.The material remains as we have them today are viewed as associated with royal and elite activity, with a context of royal courts and commercial centres. The nature of the trade was debated—was it a peddling trade or was it a market-based trade? Detailed evidence on production and exchange has not so far been easily available. There has been a shift away from referring to Southeast Asia as Greater India and recognizing its independent cultures.

The interest also turned to investigating what was adapted from Indian sources and how much was changed. It had been argued that the stupa at Borobudur was based on Indian proto-types, but this was an argument that was difficult to sustain given that possible proto-types were not available. Stupas in any case varied in size and form in different parts of Asia.

A seemingly curious parallel suggests itself in the processes by which peripheral areas in the subcontinent hosted multiple kingdoms and the same appears to have happened in many parts of Southeast Asia at approximately the same time. State-formation is the umbrella term often used. It refers to kingdoms, trade, and the adoption of the mainstream culture that was gradually modified to local conditions. Qualified brahmanas from established centres were invited. So too perhaps were various categories of craftsmen. The processes of change inherent in such mutations have to be studied more closely.

It might also help if the links were to be focused on South Asian regional connections. Physical proximity by land extended to inland Myanmar and Thailand. But Southeast Asia was more accessible by sea. Coastal India would have been the likely source, and especially the East coast. The strong links with South India are ascribed to different reasons and call upon differing processes. As a point of comparison the Indian trading links across the Arabian Sea to the West were obviously not of a similar kind since the pattern of connections is entirely different.

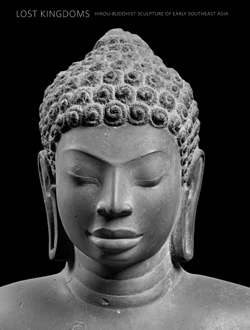

Lost Kingdoms is the handsomely produced catalogue of an exhibition held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York early in 2014. John Guy, the Curator of the South and Southeast Asian Art Department of the Museum is the author of the catalogue. Detailed discussion of each object gives the catalogue the appropriate richness of scholarship and this adds considerable value to the photographs. It is divided into sections in accordance with the display. Interleaved with this are articles by various specialists on a variety of aspects of the histories and cultures providing a context to object and region. This refers to special aspects that need highlighting, as well as technical information about the objects. The latter are mainly in stone, terracotta and metal.

Geoff Wade provides information from Chinese texts of the first millennium ad. They are far richer in information as compared to the slight references in Indian sources. The Chinese involvement with the region was initially with proximate areas in the northern parts of the mainland. When competition for trade became important the coastal areas are mentioned. The kingdoms also sent envoys to the Chinese. Champa (in Vietnam) is associated with images of deities and volumes of Buddhist sutras. Buddhist monks and brahmanas are referred to as settled in Cambodia. Mention is made of the two cities of OcEo (located in the Mekong delta), and Angkor Borei. Roman objects, such as medallions, possibly coming from Indian ports, a Han mirror and various amulets and seals, found in these city sites provide a glimpse of the trading horizon.

Dvaravati(in central Thailand) is said to have sent a diplomatic mission to China in the seventh century and also finds mention in the accounts of Chinese Buddhist pilgrims travelling through these lands. Mention is made of a centre for the study of Buddhism as well as many brahmanas from India seeking patronage. Indian scripts or their derivatives were often the origin for the writing in the local languages. Many missions to China are mentioned as coming from these lands but these may have been just visitors.

Objects dating to the mid-millennium include a strikingly beautiful dish of copper alloy from central Vietnam with a very busy hunting scene that depicts men mounted on horses and elephants hunting deer, snakes, lions, rhinos and buffaloes. The lion was not an animal from these parts and the styles reflected in the scene are mixed. John Guy suggests that it evolved from two traditions, one West Asian and the other southern Indian. Such a mixing of traditions illustrates the point that cultures need not be stylistically of single descent and that often it is in the interface between cultures that the most creative artistic expression has its origin.

The exhibition as indeed also the catalogue, directs attention to the strong local style that infused forms similar to those from South Asia. Inevitably one asks the question as to who were the craftsmen. Were they, to begin with at least, Indian craftsmen working with local craftsmen? Or did the local craftsmen immediately introduce local features into their versions of whatever came to them as sculpture from India. A more detailed discussion of craftsmanship prior to the forms exhibited would have been a useful preface. The culture of the earlier period, the bronze Dong Son culture is most impressive, but the artifacts are so different in form and function to those exhibited and with such a long break in time, that any link seems unlikely. Nevertheless a view of preceding cultures would have been of interest.

There are some features of the sculpture that are characteristically Indian, such as the consistency in giving snail-like curls to the Buddha. It almost indicates some presence of the Indian craftsman. Or was the need to follow the model so deeply imprinted that the local craftsman would not have deviated from it, even if only to give the Buddha the wavy hair that he has in Hellenistic Gandhara art?

Inscriptions are an extensive source of information. The script appears to have been adapted from the box-headed brahmi of

Indian usage. It was most likely introduced through trade

requirements and also from Buddhist texts. As Peter Skilling points out, certain Buddhist verses, such as the ‘ye dharma …’ and the ‘patitasamudpadagatha’, were recited, as and when one wished to, and were written on many kinds of materials. It is also possible that the nexus between Buddhist monks and traders on the centrality of literacy led monks to tutor people to be literate wherever they went.

The exhibits that featured in the exhibition and are included in the catalogue establish the excellence of the aesthetic that created these forms and the quality of the workmanship of much of the early sculpture from Southeast Asia. They also establish the striking contribution of Buddhism in inspiring these early forms. That Southeast Asian forms and thought gave direction to Buddhism in this period, as it did to Puranic Hinduism subsequently, needs both a comparative study and greater integration with the history of these religions elsewhere.

Romila Thapar is Professor Emeritus in History, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.