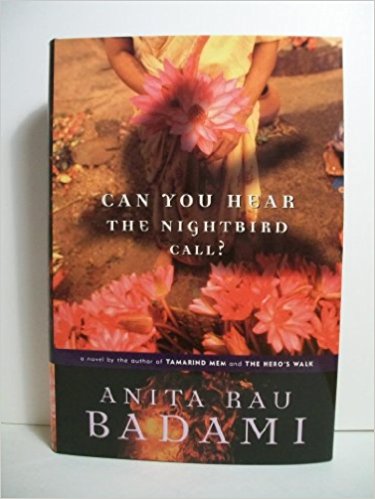

With the publication of Midnight’s Children in 1981 Indian Writing in English was finally said to have come of age. Such proclamations notwithstanding, even a quarter of a century after Rushdie’s magnum opus Indian writers in English continue to be assailed with questions such as whether they are being authentic to their culture or commodifying it for the benefit of foreign publishers, markets, and readership. Writers like Vikram Chandra and Amit Chaudhuri, among others, have written passionately in defence of the writers’ legitimate right to artistic freedom to choose whatever tropes they see fit without fear of what Chandra calls the ‘God of Authenticity’. And yet, when one comes across a novel like Anita Rau Badami’s Can You Hear the Nightbird Call? the somewhat stale critical discourse of authenticity, commodification and exoticization seems more than relevant. Badami’s third novel is set against a backdrop of watershed events in India’s recent history: the Partition of 1947; the secessionist movement in the late 1970s and early 80s for an independent Sikh homeland; the Indian army’s invasion of the Golden Temple in Amritsar in 1984; Indira Gandhi’s assassination four months later by two Sikh bodyguards; the arson, looting, and murder of over 3000 Sikhs in its aftermath, and finally, the 1985 Air India crash which killed all 329 passengers aboard in one of the worst tragedies in aviation history.

June 2007, volume 31, No 6

Wow, incredible blog structure! How long have you ever been running

a blog for? you made blogging glance easy. The

total look of your website is excellent, let

alone the content material! You can see similar here dobry sklep

What’s up to every one, it’s truly a nice for me to visit this web site, it contains valuable Information. I saw similar here: Sklep online

Hey there! Do you know if they make any plugins to

help with Search Engine Optimization? I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good success.

If you know of any please share. Thank you! You can read

similar art here: Najlepszy sklep

It’s very interesting! If you need help, look here: ARA Agency

Hey there! Do you know if they make any plugins to help with

SEO? I’m trying to get my website to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing

very good gains. If you know of any please share. Appreciate it!

You can read similar blog here: GSA Verified List