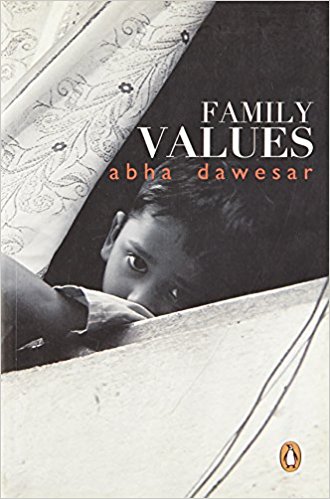

Abha Dawesar’s Family Values is written from a perspective of the young boy ‘narrator’ whose unwitting existentialist narrative questions the essence of Indian family values. Dawesar, in the novel, takes into consideration a joint family, which consists of a grandfather and his eight children—Psoriasis (son from his first wife), Six Fingers, Sugar Mills, Doctor, SSS, Paget, Poop, and Pariah. These Dickensian names are the magic realist handiwork of the boy narrator who is taught to judge people either on the basis of physical and mental traits, or status in society. Dawesar, gradually, opens a Pandora’s box, unravelling the mysterious past of every child in the family. The word ‘values’ in the title functions at two levels. At first, it ironically questions the need of the value system for the poor in the wake of disease-ridden existence. As the omniscient narrator in her introductory description of the boy narrator, who is a representative of the poor, reveals: ‘He is growing up with disease.

Not just with malaria and childhood diseases like chicken pox that strike him but with everyone else’s diseases: kidney stones, arrhythmia, leukemia, meningitis, depression, uterine bleeding, and eczema’. Not only the biological diseases but also the social diseases: corruption, bribery, discrimination and organ stealing. Secondly, the word ‘values’ in the context of family draws our attention towards Hindu sacred texts like the Dharmashastras that helped in shaping the Indological approach to the Indian joint family. Dawesar, in the novel, shows the deteriorating nature of patriarchal family with absolute power (patria potestas) in the teeth of the nuclear family and thus debunks the right-wing façade of Indian family values.

Dawesar who has won many literary prizes like the Lambda Literary Award and Stonewall Book Award for Fiction for her earlier work named Babyji, takes us back to the city of hearts, Delhi, in her latest novel. Readers who expected the same hearty adventures that were present in Babyji will be disappointed as one finds, instead of hearts, a gaping void amid a family of eight children. In fact, Delhi is depicted as a city that has lost its life and effervescence and has become embroiled with scatological imagery, a candid insinuation of deterioration and corruption. Dawesar, tongue-in-cheek, raises the metaphor of scatological imagery to a level where scatology personifies itself into a Dickensian character named Cowdung.