In normal political discussions, the conscious Ambedkarites are scaled above and admired more over the other ‘non-active’ Dalits. In the post-Ambedkar period, the Dalit Panthers in Maharashtra and the formation of the BSP in Uttar Pradesh are two prominent examples of such conscious political Dalit identities. Here the Dalit is seen as a self-realized person ready to impose the burden of social transformation. He is a revolutionary, accountable to the social cause and obedient to the promises made by the Ambedkarite Dalit movement. He is committed to a utilitarian project towards achieving complete liberation from Brahmanical servitude. This identity is therefore positive, popular and mainstream; however, this is not the only model under which all the Dalit bodies operate.

Today, Dalits are equally engaged in a range of social-political-economic activities as free conscious individuals, based on their personal desires and choices. These Dalit subjectivities are vagabond, free or often disassociated with the movement of social justice. This sphere includes Dalits that are now increasingly becoming activists of the non-Dalit political forces (including the Right Wing political outfit) or joining the bourgeois capitalist economy without any apology. They are not obedient to any one set of moral ideological Ambedkarite language but often function as free self-motivated agents to serve their rational interests.

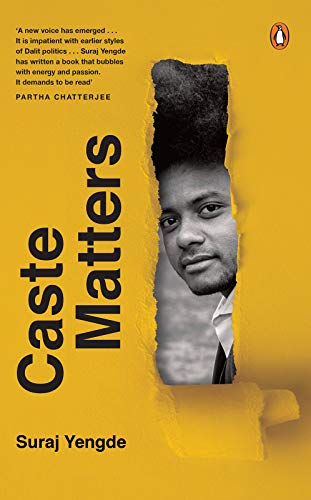

Dalit scholars use a powerfully critical tone to judge the nuanced Dalit subjectivities. Dalit literature which was influenced by the fiery and violent language of the Dalit Panthers in the 1980s was not only critical of the life worlds of the social elites but also labelled their own brethren as ‘Dalit Brahmins’ as they mimic the upper castes lifestyles in their social behaviour (Rao 2009: 197). If the independent choices made by individual Dalits are not according to the greater Ambedkarite morals, this ‘purist’ approach reserves the capacity to label them as the people who are turning the revolutionary wheel of Ambedkarite struggle in a backward direction (Teltumbde 1997). Within such discussions, the ‘neo-Dalits’ were seen as moderate constitutionalists (pp. 81-87), the prisoners of false consciousness, or the Harijans that follow the ascribed Brahmanical categories (Guru 70: 2005) or even the stooge/traitor of the community (Kanshi Ram 1982). Even the politics of BSP has been criticized for its sole concentration over political power and for neglecting the social sphere (Teltumbde 185: 2010). Suraj Yengde’s Caste Matters adopts a similar critical approach.