Cities, like dreams, are made of desires and fears, even if the thread of their discourse is secret, their rules are absurd, their perspectives deceitful, and everything conceals something else.

– Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

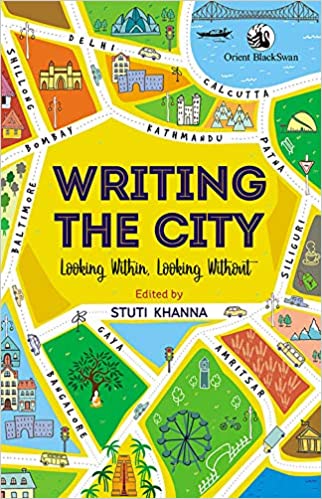

Do the cities with their sensorial excesses of sights, sounds, smell, and touch shape the way writers experience their quotidian lives or do the bodily experiences of writers as inhabitants of cities lend the cities their unique character? Straddling these two perspectives, the slim volume comprising fourteen essays by Indian English writers drawing from their personal associations with and physical and metaphysical responses to the cities they write about opens fresh perspectives about the cities and their relationship with the writers. Each writer engages with their geography in their unique way and the city responds in commensurable measure by unfolding itself in all its spectacular to banal spatio-temporality in accordance with the quest of the writer.