This is an engaging, poignant and important autobiography. It will be a serious ‘reality check’ for all readers! Biswas is a wonderful story teller, his almost ‘matter-of-fact’ style engages the reader and virtually transports him or her to the rice paddies, river banks and muddy creeks which are indelibly part of Biswas’s formative years.

At times the story envelopes the reader in powerful and poignant emotional recollections which would be quite difficult to handle if they were overly dramatized. Manohar ‘tells it like it is’ in simple language, his honesty and forthrightness coming through on every page. We experience the dignity and genuineness of this man in an almost palpable way. It is amazing, considering the deprivation suffered, social rejection and poor living conditions of the dalits (namashudra or untouchables) that Biswas’s story does not focus on bitterness or hatred. There is at times an underlying sadness expressed in the chapters—how could there not be?—when one group of humans have been treated in such a detestable way by other groups within the caste system.

The caste system incidentally was not originally a state instigated abomination but one of religious beginnings in the Vedas. ‘The Vedas itself stated the stratification of four categories of castes, such as the brahmins, the kshatriyas, the vaishyas and the shudras [Rig: 10.90.12]’ (p. 96). The ‘partition’ of the nation (Bengal) was used by a minority for their own purposes, ‘They were successful in using religion blindly for their own selfish interests’ (p. 80). Similarly the treatment of black Africans, slavery and Apartheid by so called Christians was a result of deliberate and inaccurate interpretation of certain Christian scriptures.

Surviving In My World is an important book because it exposes the caste system for what it really was (and in some respects still is), it presents the living conditions of dalits in a day-to-day quest for mere survival, which feeling persons could never condone nor tolerate if they were fully aware of the dalit’s plight. By publishing his story Biswas will reach a large number of people in both India and globally who previously may have had no real idea of the extent of suppression and oppression of the untouchables, myself included. As R. Azhagarasan says in the beginning of the book; ‘Manohar Mouli Biswas’s autobiography is significant not merely in expanding the dalit canon but in locating the biased vision of the seemingly secular Bengal mainstream.’

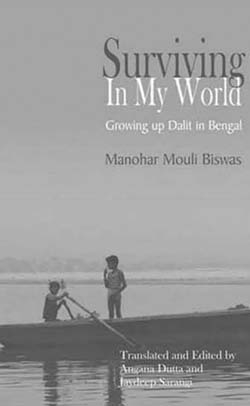

A little about the content of the book. It has in my opinion a skilfully designed cover which is both captivating and truly expresses the purpose of the book. Amar Bhubane Ami Thaki is the Bengali title of this book originally written by Biswas in his native language. This version in English, brilliantly translated by Dutta and Sarangi consists of explanatory notes on the Bengali calendar, kinship terms, and a very useful glossary. There is an introductory note by Manohar; a foreword by Sekhar Bandyopadhyay, introduction by the editors; and a most enlightening and engaging interview with Biswas by Dutta, Sarangi and Gurav.

Many of the passages in the chapters give the reader a deep understanding of the dalit’s world and just how isolated both geographically, culturally and socially their world was. Referring to dalit songs and his boyhood companions, ‘Their illiteracy, their poverty, did not sour them and they remained engrossed in their world. They had sculpted their world in their own style, and just as the outer world had provided no entry there, they did not step out of their world’ (p. 38).

Manohar compares the dalits’ lives to that of the water hyacinth, very resilient but despised, neglected and uncared for. This plant grows in the mud prolifically and was ever present in the waterways around the villages. These waterways were in a sense the life blood of the dalits as they enabled the rice paddies to yield good crops (monsoon disasters notwithstanding) and were also inhabited by fish which Manohar relates how he loved to catch.

Manohar is at pains to point out that this book is not his complete autobiography. Further on in the story he includes details of his successful education against all odds, his marriage and children who did not experience his formative years growing up as a dalit. ‘This autobiography is my autobiography, my father’s autobiography, my grandfather’s autobiography, my great grandfather’s autobiography. This is the autobiography of remembering the bygone memories of my community’ (p. 78).

Those not living in India and Bangladesh would be forgiven for thinking that the lot of the dalits had been vastly improved in recent years but as Manohar relates this is not the case. ‘There is no greater pain than hunger to the starving. There have been commendable developments in government policies aiming at dalit empowerment and much has been achieved as well; however, large sections of dalits still remain trapped in conditions of dire deprivation. Many of them remain homeless, without any shelter’ (p. 79).

In the interview section of Surviving In My World the interviewers ask Manohar, ‘Don’t you desire to get all your work translated so that internationally people can be inspired by your writings and shoulder the responsibility of emancipating the dalits?’ His answer: ‘I don’t believe in it because of the fact the state-level people do not recognise me. Then how can I be known internationally?’ (p. 108) I feel Manohar may be in for a pleasant surprise! He has worked tirelessly to improve the dalit’s situation especially through his literary creations, including his recent book of poetry The Wheel Will Turn, and now this heartrending autobiography. I only hope that the publication and global exposure of Manohar’s books (despite his reticence), and also the reviews of these books will help the dalits gain the freedom that many of us simply take for granted.

Rob Harle is a writer, artist and academic reviewer.