To write is to demonstrate a principled willingness to be judged. The writer knows that her neck is on the line but she lives with this awareness and continues moving towards something more honest. She knows she will never be able to capture the entire human being, that her words—her most trusted aides—will fail her eventually, but she continues inching towards that failure ensuring that she fails well. In every failure she finds her reasons for embarking upon another failure, of a different and, preferably, better kind. With every failure, she presents a novel philosophy that lies underneath the toil of human existence, a unique frame of understanding human moments, and a case for accepting their mysterious workings as opposed to dissecting them.

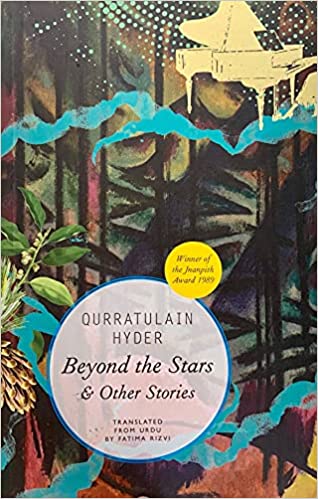

Qurratulain Hyder (1927-2007), one of Urdu’s finest writers, always knew that she was risking her neck. She started writing at a time when progressive writers had fixed the meaning, purpose, themes and content of literature. Hyder too wrote about contradictions, crises, suffering, struggles, loss, and multiple shades of unrequited love, but her setting was markedly different. Instead of directing her creative faculties towards the wretched of the earth, she took it upon herself to focus on the cursed of the land, the feudal families of Awadh. Drawing on her personal experience, she wrote about men and women of the upper echleons of Awadh, their trials and tribulations, struggles vis-à-vis love and life, the cultural richness of this feudal landscape, its cohesiveness and contradictions. She was criticized for elitism, sympathy for feudal and bourgeois lifestyle, and a love hopelessly contaminated by shallow moral standards, bereft of sexual desire. But Hyder did not judge her characters and continued with her literary endeavours.