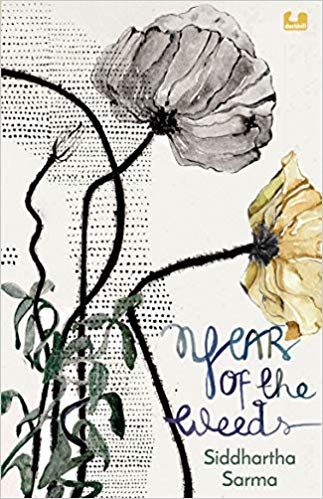

Year of the Weeds by Siddhartha Sarma is a modern-day parable. This Young Adult (YA) novel has a deeply affective register such that it neither underplays nor overcompensates for its political and social understanding and representations. It would not be an exaggeration to call the novel a sociological fiction in terms of its tenor and treatment of the little biographies of the characters in the novel. Sarma has treated the issue of marginalization, which is the central theme of this novel, in a way that the ‘small voice of history’ becomes the voice of sanity and wisdom. The novel’s intention seems to be the recovery of the lost voice of the repressed by foregrounding folk memory and wisdom. It problematizes the metanarrative of development by questioning bureaucrati-zation of everyday life, stripping it of its meaning for ordinary people.

Based on the lives of the Gonds of Deogan village of Balangir district in Orissa, the novel traces the contours of corruption and the various vile machinations of the government officials (which seem true-to-life) that threaten the peaceful coexistence between the tribe and nature. The novel becomes more relevant today for its conscious interventions on the gendered nature of narrativizing movements and organizations.

Korok, the protagonist is a young teenaged boy whose talent lies in being the best gardener in Deogan. The lives of the Gonds here take a turn for the worse, when one day, the government decides to allow a private corporation to dig up a mine in the Devi Hills for its bauxite deposits. The hill is sacred to the Gonds in more ways than one. It is the abode of the departed (halankot) as well as of the many ‘small gods’ (pen) who look after the well being of the living Gonds of Deogan. Korok, the scrawny Gond boy takes up the duty of his father as a gardener at the District Forest Officer’s (DFO or epho as the Gonds call him) residence. He assumes this duty upon the arrest of his father on the false charge of being a timber thief. The villagers are pitted against the corrupt Superintendent of Police of Balangir district, S Patnaik. The ‘S’ here is taken by the Gonds to stand for Sorkari (p. 12). The corrupt legal system in Balangir district has for long troubled the peace-loving, law-biding Gonds who are routinely arrested on false allegations, and are, in most cases, not let free. One knew in Deogan that, ‘going to jail was not the same thing as being a criminal’ (p. 129). In Balangir as well as in the country, expecting justice for the marginalized is a foregone conclusion since, ‘even gods have their ranks and Gond gods, like Gonds did not matter’ (p. 112).