How do you write about violence without being didactic or banal? Living as we are today in a world spiralling into deeper gyres of conflict, how do you represent the slow unravelling of the self fronted with pain and loss beyond control, beyond comprehension, beyond understanding? Bombarded with a constant battery of sound and image, of urgent words tearing across our networked minds, it is increasingly difficult to sustain interest—to say nothing of outrage. How, then, do you evoke rampant chaos and confusion without resorting either to the thickness of the digest or the sensationalism of the newsflash?

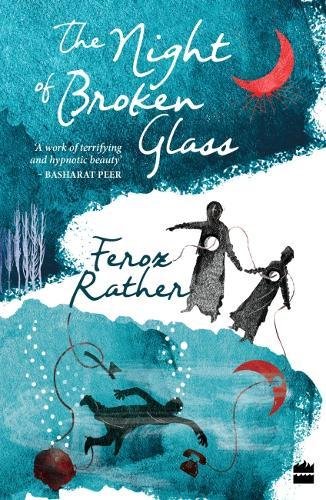

The Night of Broken Glass, Feroz Rather’s maiden offering in book form, provides some cues. Comprising thirteen short narratives set over two decades of incessant bloodshed in Kashmir, it is a significant statement on not just how to imagine the Valley beyond familiar tropes of victimhood and violence but also how these material realities inflect the form and function of narrative and plot emergent from such contexts. Rather’s achievement lies in being able to carefully and potently humanize the brutal recalibration of the ordinary and the everyday amidst the struggle between militancy and counter-terrorism: what appear as a result are disturbingly believable vignettes on the experiential realities of this inter-generational battle for Kashmir.

The book begins with the hint of a closure: at a critical finality, moving towards a beguiling absolution. ‘The Old Man in the Cottage’ dramatizes revenge in a quietly deliberative fashion, juxtaposing the lasting agony of torture against pity for the dying in the last throbs of life. Is an eye for an eye, stone for a stone, life for a life, the only meaning of revenge, or is destiny itself an agent of vengeance? Corrupted both in mind and body by the lives he has destroyed, Inspector Masoodi sputters to a neglected and painful end: the cancer that consumes him is as much of his lungs as of his soul, turning him into a decrepit, unloved picture of sheer helplessness.