For nearly a millennia, the qissa has been one of the most fecund genres in the written and oral literatures of Arabic, Persian, Urdu, Punjabi and beyond. It can be a short tale, such as the popular qissa of Chhabeeli Bhatiyarin, so acutely analysed by Kumkum Sangari (in India’s Literary History: Essays on the Nineteenth Century, edited by Stuart H Blackburn, Vasudha Dalmia) or it could be long like the Bagh-o Bahar alias Qissa-e Chahar Darwesh by Mir Amman, itself purportedly based on a creation by Amir Khusrau. Ever since its publication by Fort William College in the early 19th century, the latter has continuously been a staple of Urdu literature syllabi in schools and colleges. For his telling of a qissa in English, Musharraf Farooqi travels back in time to one of the most apocalyptic moments in world history: the sack of Baghdad by the Mongols in 1258, which, in a sense, ended the world as it then existed. For until then Baghdad was not only the political and economic centre of the world, not just in imperial terms or in terms of trade and wealth, where all roads did lead to Baghdad, but also in terms of an efflorescence of the Islamic Renaissance and its intellectual and cultural achievements which remain unsurpassed. Needless to add, this is also the physical and cultural landscape of the Alif Lail Wa Layla, aka The Arabian Nights, undoubtedly the most famous qissa ever told.

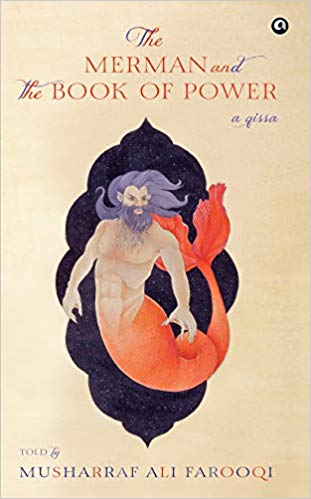

The principal figure in this qissa is the real historical figure of Qazwini, a cosmographer, philologist, scientist and philosopher and the setting is Baghdad, soon after the Mongols raid the city. Like other intellectuals of his time, or of ours, Qazwini is trying to come to terms with the new political revolution and to readjust his relations with power. Qazwini, a renowned scholar, is trying to study a recently captured Merman as part of his quest to understand the marvels of creation, the Ajaib and Gharaib, the wondrous and the supernatural, as reflected in his actual encyclopaedic work, Ajaib al Makhluqat wa gharaib al maujudat (Marvels of Things Created and Miraculous Aspects of Things Existing). In order to accomplish his ends he manoeuvres to have a beautiful slave-concubine, Aydan, his one-time lover and now the Governor’s mistress, to mate with the Merman. As Mushfarraf writes, ‘Qazwini’s theory of existence defined the human as a plant by its element of development, a beast by virtue of feeling and motion, and an angel by virtue of his knowledge of the essence of things…the study would be a crowning addition to his compendium, Qazwini felt, bringing together his many theories about the creatures, and the various stages they represented in the table of Creation.’

At the same time Qazwini is also after The Book of Power, an ancient work of occult mystery captured from the deep recesses of a Byzantine monastery after the fall of Amorium to the Abbasids. The Book of Power with its prophecies about Alexander and the mythical creatures Gog and Megog portends the end of the world and acts as a guide and warning to its possessors. Rulers hanker after the possession of the book, but are also eventually subjugated by it. Occult, apocalypse, esoteric knowledge, mysteries of creation are all brought together with the fascinating story of the Merman Gujastak and Aydan’s relationship and Qazwini’s own emasculated and jealous fascination with its contours.

The Abbasid era, of course, remains one of the most illustrious periods of intellectual growth and discovery in human history. Its achievements in astronomy, philosophy, natural sciences and literature provided the basis for the European renaissance of the 16th century. Many of those hallowed figures make a direct and indirect entry into this story. Qazwini himself, Tabari, one of the earliest historians of Islam, Masudi, Khwarizmi and the many oriental and occidental legends and myths associated with Alexander, the Sikandar Zulqarnain (Alexander the Bicornous) coexist with the great Abbasid Caliphs such as Mamun and Wathiq. As befits a qissa there are also supernatural creatures and events galore. The late great Urdu writer Intizar Husain, one of the great purveyors of the qissa in modern Urdu literature, constantly lamented the Anthropecenic turn in literature after the rise of modern Humanism, when other creatures and forms of existence disappeared from literature. This was very unlike the scenario in the pre-modern era in works such as The Arabian Nights, the Jatakas, the Panchtantra and the Katha Sarit Sagar. In literature, as in the world, man must coexist with other creatures and other forms of existence, which as God has averred again and again in the Quran, are there for us to study and reflect and to marvel on this magical creation and the powers of the Creator. As the Quran states in the Surah Yaseen,

Subhanallazi khalaqal azwaja kullaha mimma tunmbitul arzu wa min anfusihim wa mimma la ya’a la mun

‘Exalted is He who created all pairs from what the earth grows and from themselves and from that which they do not know.’

This sentiment is echoed by Shakespeare when he has Hamlet say to Horatio,

‘There are more things in heaven and Earth, Horatio, / Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.’

In order to tell this qissa Musharraf has mined innumerable classical and modern resources, some in their Persian and Urdu translations and which were first published in the 19th and early 20th centuries by the fabled Nawal Kishore Press, with which he has an intimate connection. Writing this qissa on and about polymaths necessarily required the writer to be an erudite polyglot and in that respect Musharraf Farooqi is one of the most accomplished writers of South Asia. His marvellous translation of the classic Dastan-e Amir Hamza was a tour de force and his command over English, French, German, Persian, Arabic and Urdu was displayed in full force in that as well as his translation of the first volume of the most famous chapter of the long Hamza cycle the Tilism-e Hoshruba. Since we share a surname, I have often gladly received mistaken compliments for being the wonderful translator of the above two. In addition Musharraf’s other major accomplishment lies in creating an online comprehensive Urdu thesaurus, as in addition to his other translation projects with the Urdu Project. His columns in newspapers in India and Pakistan continuously dazzle us with the stories he mines from such diverse sources as Sufi hagiographies, bibliographical dictionaries, manuals and other esoteric collections. As a storyteller, his work with children is also admirable. There are few writers in South Asia who can match this kind of multilingual fluency and erudition, and fewer still who can match that with a range of creative output that extends from fiction, translation, dictionary making, and practical engagements with pedagogy and performance. There is much to admire in and learn from in this wonderful book, but there is a cavil too. As a qissa it doesn’t excite our curiosity enough, we are not dying to know what happens next, and the pace of events is sometimes a tad too slow for the genre. Without that compelling interest a qissa doesn’t stand. But perhaps that is inevitable when one converts an essentially oral genre into something to be read of a page.

Mahmood Farooqui is best known for reviving Dastangoi, the lost Art of Urdu storytelling.

[/ihc-hide-content]