When ‘Hindi Crime King’ Surendra Mohan Pathak took the dais at the third annual Noir Literature Festival at the Oxford Book Store in Delhi’s Connaught Place in January 2017, he faced a rapt audience of fans tightly packed into and spilling out beyond the rows of folding chairs set up at the back of the store. Pathak grinned alongside festival organizer Namita Gokhale as the two unwrapped and posed with the hot-off-the presses release from HarperCollins India, Framed, a translation of Pathak’s Hindi novel Hazaar Haath, originally published in 1998. This release was part of a recent reclamation of Surender Mohan Pathak by a more elite—and in many cases Anglophone, at least in terms of literary reading preferences—urban Indian audience newly smitten with Hindi pulp fiction; Pathak was recruited in 2013 to be the brand ambassador for the new Harper Black (an imprint of Harper Collins dedicated to crime fiction), which began reprinting many of Pathak’s most popular novels in the original Hindi while also commissioning their translations (while not, it should be noted, bothering to credit the translators). The covers were more modern, the paper quality much improved from the grey pulpy pages of the mainstream pulp publishing houses in Old Delhi and Meerut, and the price was bumped from 40 rupees to 125. Sales soared, and there soon followed boxed sets, branded merchandise, and a new lease on life for Hindi pulp fiction.

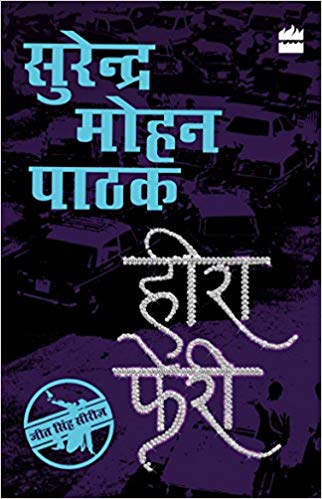

Now we have Hira Pheri, his 297th novel overall, and the 11th in his Jeet Singh series of books, but the first of Pathak’s novels to be published simultaneously in Hindi and English (as Diamonds For All). In a personal note to readers at the start of the Hindi edition (and absent from the English one), a traditional practice of Hindi pulp novelists who maintain a close connection with their readers, Pathak appeals for his readers’ honest reactions to this dvibhaashi upakram, or bilingual enterprise. He explains that Diamonds For All is not a traditional translation (though the English edition calls itself such), but a new novel he himself wrote in English, a simultaneous version of the Hindi Hira Pheri. He goes on in this note to regale his Hindi readers with a discourse on wills and inheritances, a rumination on the responsibility of the living to plan for their death that eventually turns into something like a standup routine full of outlandish stories and bawdy jokes. It is a gift of Pathak to his Hindi readers, a short essay in his own humorous voice (he is also the author of several joke books), deepening his personal connection with his fans, a connection that is notably absent from the English edition. Nor does Diamonds For All include his email address, or the url of his most popular fansite, as the Hindi one does. These invitations to personal connection and engagement are reserved for his established base of ‘SMP-ians’, and they all read in Hindi.

The plot of both Hira Pheri and Diamonds For All is a dizzying thrill ride over the course of seven days in Mumbai during which the reader chases a cache of 400 diamonds smuggled in from Dubai for Amar Nayak, described on the novel’s first page as ‘Mumbai underworld ka bada don tha, aur mavaali tha, smuggler tha, racketeer tha.’ The multilingual character of Hira Pheri, indeed all of ‘Hindi pulp’ is evident from the outset; the novel also includes a Mumbaiya shabdaavali, or glossary of Bombay-isms. The majority of this multilingual richness is obscured in Diamonds For All, but Pathak does retain some Hindi vocabulary for terms specific to the lexicon of Indian gangsterism (bhaigiri, baap, mawali).