Toolika Wadhwa

FIR MILENGE

By Ahmad Raza Ahmadi. Illustrations by Nahid Kazmi

2018, pp. 22, `150.00

KYA TUM HO MERI DADI?

Text and illustrations by Sanika Deshpande

2020, pp. 28, `130.00

CHAAR CHATORE

By Virendra Dubey. Illustrations by Nabreena Singh

2019, pp. 46, `130.00

NEEND KIS CHIDIYA KA NAAM HAI?

By Rajesh Joshi. Illustrations by Bhargava Kulkarni

2020, pp. 36, `160.00

RANU… MAIN KYA JANU?

By Asgar Vajaahat. Illustrations by Atanu Roy

2018, pp. 18, `90.00

BHOOTON KI BARAAT

Text and illustrations by Barkha Lohiya

2020, pp. 24, `120.00

KISSU HAATHI

Text and illustrations by Manikza Museel

2018, pp. 25, `170.00

ANOKHA STHAPATI (THE MASTER BUILDER: A TRAGEDY IN FOURTEEN PAGES)

Text and illustrations by Nachiket Patwardhan

2019, pp. 14, `80.00

KAISA KAISA KHANA

By Prabhaat. Illustrations by Alan Shaw

2019, pp. 30, `90.00

BIKSU

Text and illustrations by Rajkumari

2018, pp. 121, `600.00

JAB MAIN MOTI KO GHAR LAYI

Text and illustrations by Proiti Roy

2018, pp. 21, `90.00

AANKH KHULI AUR SAPNA GIR GAYA

By Shashi Sablok. Illustrations by Uma Devi Ketha

2020, pp. 16,` 100.00

TARIK KA SOORAJ

By Shashi Sablok. Illustrations by Tavisha Singh

2020, pp. 20, `110.00

KHAI DAAL/PEETH PAR BASTA

By Shivcharan Saroha and Nagesh Pandey ‘Sanjay’. Illustrations by Devbrat Ghosh

2018, pp. 12, `50.00

BILLI KE RAAT-DIN/ GARMIYON MEIN EK BAAR/ RAJA AUR AAM INSAAN/ROBBY

All four written and illustrated by K.G.Subramanyan

2020, pp. 16, pp.20, pp.22& pp.20, `80.00, `90.00, `100.00 & `90.00

MOR DUNGRI

Text and illustrations by Sunita

2018, pp. 20, `100.00

BAKRI KE SAATH

By Shyam Susheel. Illustrations by Bhargava Kulkarni

2018, pp.8, `40.00

CHAND KI ROTI/ CHEENTI CHADHI PAHAAD

By various authors. Illustrations by Proiti Roy

2019, pp. 16 each, `65.00 each

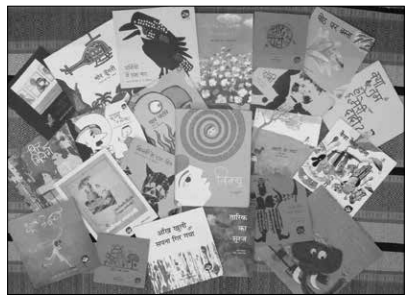

All published by Jugnu Prakashan, an imprint of Takshashila Education Society, Bhopal

Children are often seen as insulated from the world’s worries and continue to live in a world of make-believe and fantasy. This world is far removed from life’s realities that can be harsh and damaging for the child. Print and electronic media developed for children similarly present stories that are not rooted in reality. These stories serve to develop wonderment, excitement and trigger imagination and creativity. But in sheltering children from the complexities of life, we deny children’s capabilities to handle what they observe around them. The Jugnu series works towards breaking these stereotypes and bringing stories closer to the sweet and sour world of children. Takshashila works at the grassroots to bring about a change in the community, with the community, in the fields of education, livelihood, women’s empowerment and preserving the heritage of Indian art and craft.

Lohiya’s Bhooton ki Baraat is a story of a young man fascinated by ghosts. He ends up marrying a ghost and starting a family with her. The story captures a child’s imagination and fosters curiosity about the paranormal and the unknown. Written as a story in a story, the book documents a folk-tale from Uttarakhand. The dying art of story narration and changing family structures have led to many folk-tales remaining lost forever. Stories of this kind help to document folk-tales, although these tales will not change with each narration like grandmother’s tales would have. The story also serves as a trigger point for discussion on superstitions and beliefs. I narrated this story to my eleven-year old niece. She was enchanted with the world of ghosts and was curious about the children born to a ghost and a human. Immediately on the completion of the story she exclaimed, how wonderful it would have been if it was the mother who was the ghost! Her responses indicate the interest the book generated in the mind of a child.

A similar effort towards posterity is also evident in Anokha Sthapati. Patwardhan weaves a story of grandiosity in which kings fund the construction of castles and prevent the master builder recreating a masterpiece. The story has the potential to create a sense of awe in children but it is also a story of human emotions. A practising architect and painter, Patwardhan’s illustrations in the story are intricate and appealing.

The Jugnu series deserves appreciation for being open to experimentation in the content as well as format of publication. Patwardhan’s book is published bilingually in Hindi and English, and serves the valuable purpose of being linguistically inclusive and fostering learning two languages. Peeth Par Basta and Khai Daal are four-line, tiny tales that can be read out to children. The two stories are combined in one book. The book introduces a new format as it can be read from both ends. Beautifully illustrated by Devbrat Ghosh, the book provides full page pictures, in bold colours to appeal to children.

The poem collection, Chaar Chatore, by Virendra Dubey, illustrated by Nabrina Singh, appeals to young and old alike, with a large parrot on its cover page. Besides the visual appeal, the poems use everyday language to talk about ideas that children observe around them. The poem Pahiyon ki Khoj, talks about the invention of the wheel and the joy that speed has brought. Another poem talks about the fun in the mundane such as the stomach ailments of a grandfather (Paddu). The simple rhyme scheme used in the poem holds potential for merriment for children but also addresses some serious issues. In the poem Pakaudi, the poet talks about changing rainfall over a period of decades and grandmother’s tales of enjoying fritters.

The poem collections illustrated by Proiti Roy provide a different visual, with black drawings on brown paper. An artist, educated at the Vishwa Bharti University, Roy’s simple drawings depict emotions in imagery put forth through a collection of short poems written by different poets. The poems in the two collections (Chaand ki Roti and Cheenti Chadhi Pahaad,) are particularly useful for primary school children to read and recite together in the class, or during play time.

A different format of poetry can be seen in Neend Kis Chidiya ka Naam hai. The nineteen poems in this collection introduce the format of free verse to children. The poems bring freshness to looking at everyday phenomena. The poem Atirikt Cheezon ki Maaya will lead one to think of the impact of consumerism and maximalism. The poem Cheentiyan reflects on the insecurities of human beings when they use metaphors that trivialize an ant’s existence. In another poem, Bachchon ki Chitrakala Pratiyogita and Bachche Kaam Par Ja Rahe Hain, the poet reflects on the world created by adults where there is little space left for children to play. In line with the themes, the illustrations are more complex than in other books. The poems will appeal to older children and can be effectively used by teachers and parents of pre-adolescent and adolescent children to discuss the world around them.

Kaisa Kaisa Khana by Prabhat, illustrated by Alan Shaw, explores the different meanings and usage of the word Khana. Another endeavour exploring the wonders of language is Fir Milenge, illustrated by Nahid Kazmi. It presents a child wondering if words disappear when objects do. The relationship between ideas and language is put forth in a format that is easy for children to comprehend and deliberate on.

Several books in the Jugnu series address the curiosity and imagination of children. Tarik ka Sooraj uses water colour art to depict the story of a young boy who wishes to play outsider in the dark. Night life and its impact on others around us is hidden in the light-hearted anecdote of Tarik placing the drawing of a sun on the tree outside his house. The simple narration makes the complex idea of why the dark night is as important as day light, easy to comprehend. Sablok uses emotive language and ends with an open-ended question: would the reader/child like to place his/her sun or moon in the sky? The story thus provides space for further engagement with children and allows them to let their ideas flow freely. A similar, although addressing more serious issues, is the writing of Vajaahat. In Ranu, Main Kya Janu? Vajaahat presents the dialogues between a father and a son as the son asks significant questions that range on issues of animal rights, superstitions, social equity and gender biases. The questions are unanswered and leave space for discussion. A similar discussion can also be held on the basis of Lohiya’s Bhooton ki Baraat. The ghost in the story disappears as soon as she starts to speak, indicating the lack of space for women with voice in society. The story can also be used to talk about how folk-tales are created and carried forward across generations.

Another significant dimension of a child’s life that is covered through several books is relationships of children with others around them. While Aankh Khuli Aur Sapna Gir Gaya explores the relationship between a mother and daughter, Bakri Ke Saath, illustrated by Proiti Roy, explores the friendship between children and animals. Kissu Haathi is the story of an elephant who loves to narrate stories. While all his other friends get bored of his stories, an ant provides her undivided attention to him and enjoys his story. The story depicts the beauty of friendship through the world of animals. Another attempt at exploring relationships is through Kya Tum Ho Meri Daadi? Trained in illustration at Riyaz, a joint initiative of Ektara and Tata Trust, Deshpande uses her illustrations and story-telling to depict the inner world of the child. In this story, a young girl deals with the death of her grandmother. Her father tells her that her grandmother would return in some other form, and the young girl wonders what natural form her grandmother would take. The book is invaluable in helping children deal with difficult emotions as well as for adults to broach the subject of death in talking to children. Proiti Roy’s illustrations, in Jab Main Moti ko Ghar Laayi, transcend the use of words for story-telling. The twenty-page book contains only one sentence. The book can serve many purposes. It can be read aloud to young children and can be used for picture description and story creating by older children. Kya Tum Ho Meri Daadi? presents questions on the back cover to encourage discussion, sharing and imagination in children.

Kissu Hathi is also significant for the different imagery that it presents. The depiction of the animals in the book is through patchwork illustration, introducing a different usage of material to children. Mor Dungri and Biksu introduce children to the traditional art form of Madhubani paintings. The intricate drawings are attractive and contextualize the story to make it relevant for the child. In Mor Dungri, Sunita addresses the very important issue of urbanization and its impact on the relationship between humans and the natural environment. Biksu is an illustrated book set in Jharkhand and based on a letter by Vikas Kumar Vidyarthi. The book uses the dialect of Hindi that he spoke to narrate the tale of a young boy adjusting to hostel life. His coping mechanisms and inner conflicts and dilemmas have been presented in his voice. The book can be a source of cathartic expression for children living in hostels.

The books written and illustrated by KG Subramanyan address issues of identity, adaptation to modern life, and media and propaganda. While Billi Ke Raat Din covers the everyday life of a cat, Robby talks about how a child adorns many roles as he grows up. Both the books serve to help children to think about their own lives and find what holds their interest. Garmiyon Mein Ek Baar is an adaptation of the thirsty crow. The story serves to understand and possibly bridge the intergenerational gap as the crow devises new strategies to reach the elusive water, this time available in a glass bottle instead of an earthen pot. On reading the book, my niece wondered about alternative strategies that the crow could have used to break the glass bottle or making it fall so that water would pour out. In Raja Aur Aam Insaan, Subramanyan discusses the use of media to promote the king and prevent citizens from thinking of an alternative life. In contemporary times, this holds potential for tremendous discussion with children and adolescents alike.

It is important to recognize what an exposure to poems and prose that do not relate to the context of the child can do. Adichie, in her TED talk ‘The Danger of a Single Story’, talks about how she grew up reading about white characters and environments that were far removed from her context. At the beginning of her writing career, she wrote similar stories that she did not see around her. Reading contextualized stories allows the child to develop a sense of pride in the place that one belongs to. When writing children’s literature about a culture and using illustrations that are steeped in art forms that belong to a particular place, not only do writers/artists save a dying culture, but also build awareness and take pride in who they are. Takshashila Education Society has been able to initiate a movement in this direction.

References:

Adichie, C. (2009). The danger of a single story

. Retrieved: https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare