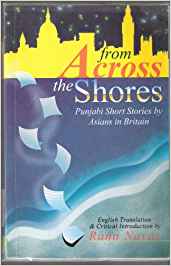

It’s one of those unsettling questions endlessly asked: what makes immigrants stay on in their land of adoption (generally western) if they end up unhappy, can’t strike roots, feel alien, homesick or abused; if the culture shock is hard, if memories of the motherland wring the soul, if the sunshine and yellow mustard fields of Punjab that put a song in your heart are so swiftly removed by England’s grey skies and fickle rain? If, as writer Gurnam Gill says in his short story ‘Trees in Kew Gardens’: “We are all trees of Kew Gardens. Our roots don’t run deep…it just doesn’t happen, or perhaps we don’t really know how to do so. In Kew Gardens, you do find mango trees, but they don’t ever flower.” From Across the Shores: Punjabi Short Stories from Asians in Britain (a project sponsored by Charles Wallace India Trust fellowship) is an inaugural offering in English of short stories by first generation immigrants-turned-writers. In a reflective introduction (which appears to place on the stories greater critical analysis and commentary than they warrant), translator Rana Nayar explains as well the dynamics of the Punjabi immigration experience as to why he selected the works he did.

April 2004, volume 28, No 4