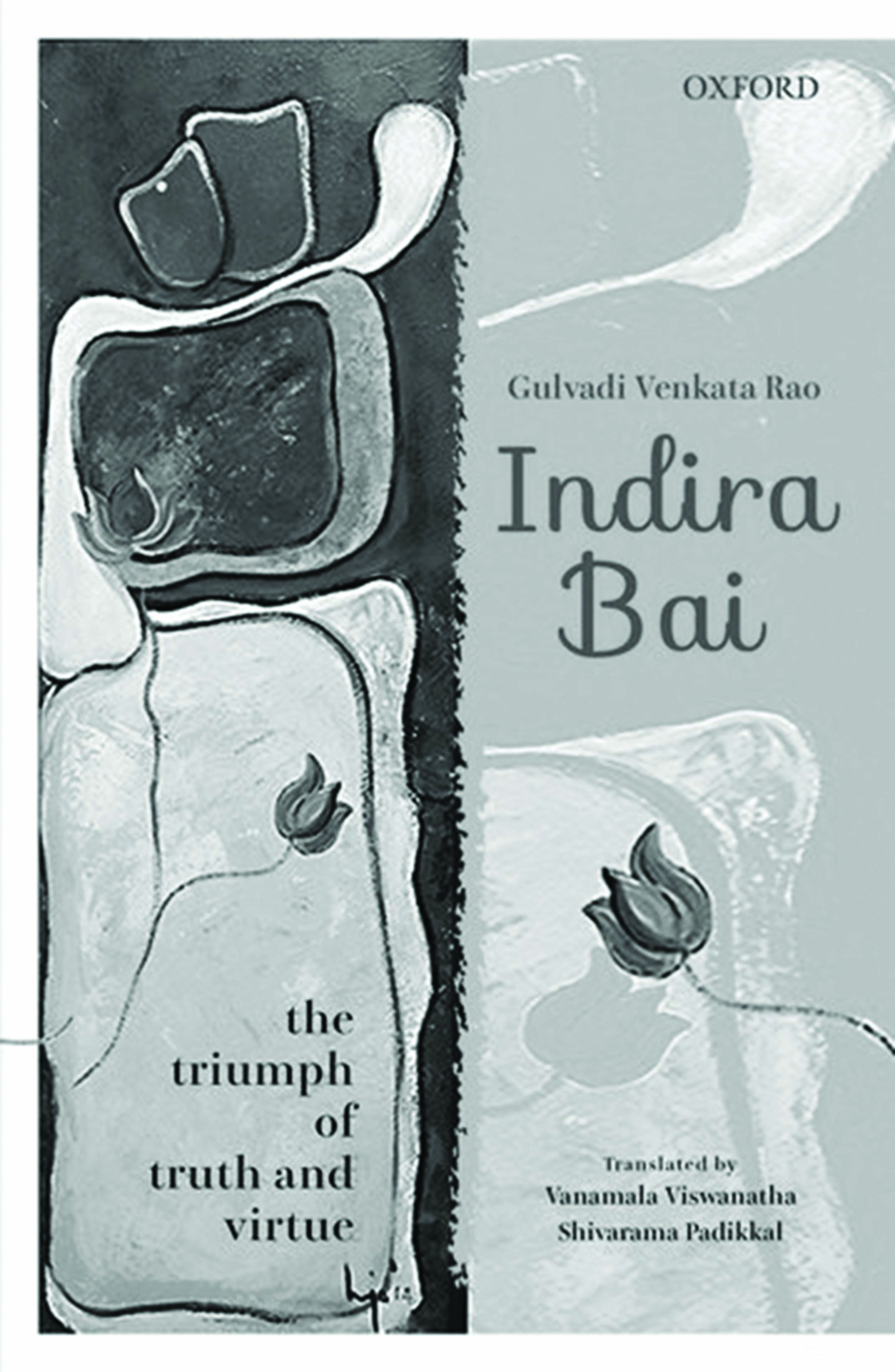

The first Kannada novel, Indira Bai or The Triumph of Truth and Virtue, has been recently translated into English, for the second time, by Vanamala Viswanatha and Shivarama Padikkal. Originally published by the Basel Mission Press, Mangalore, in 1899 the novel was first translated into English in 1903 by ME Couchman, the collector of South Canara. The new translation is especially notable for two reasons. Firstly, it succeeds in preventing the English translation from becoming opaque to the multilingual social registers embedded in the original Kannada novel. Since the use of five different languages in the Kannada novel marks out the hierarchies of caste and class in the social world from which the novel emerged and indicates the intersections and overlapping of different epistemological worlds, the success of the translators in making this overt in the English translation is laudable. Secondly, through the extensive and appropriate use of footnotes which provide glossary and reference for concepts embedded in the indigenous life world, titles that signify socially specific status positions, terms denoting caste practices which do not have an English equivalent, the translators succeed in the project of translating across languages, a historically specific cross section of a socio-cultural world in all its dense materiality.

The novel is important for its regionally inflected, caste located and historically nuanced articulation of the transformations that were taking place within the Saraswat Brahmin community, to which the author Gulvadi Venkata Rao belonged, in the nineteenth century. The re-formation of Indira, the protagonist of the novel, takes place at the nexus of several social worlds that historically overlapped as well contested with each other. In the nineteenth century, the narrative crafting of these intersections of different epistemological and socio/cultural worlds was being worked through the new genre of the social novel, while the production and dissemination of the novel was enabled through the newly instituted site of modernity—the printing press. The Basel Mission Press in which Gulvadi’s novel was printed, also printed textbooks, the first Kannada newspaper and publications of the colonial government. Thus, it was an important site for the dissemination and construction of modernity in the Canarese region. Indira’s own progress towards a reformed femininity is seen as being initiated through her reading of the books published by the padres.

The other significant influence on Indira is the Chitpavan Brahmin convert Christian and social reformer Pandita Ramabai who was born in South Canara and later migrated to Maharashtra where she set up her institutions for women in Bombay and Pune. Much to the consternation of her mother Amba Bai, Indira reads the books of the padres as well as Stree Dharma Neeti authored by Pandita Ramabai. In a thinly veiled reference to Pandita Ramabai and her school for Brahmin widows Sharadha Sadan, Indira’s foster-father Amritha Raya sends her to a residential school for widows in Satara, Saraswati Mandira, set up by a woman called Pandita Anandi Bai, where, according to Amritha Rao, ‘The right code of conduct for women (Stree Dharma Neeti) is taught to young widows.’ Bhaskara’s brilliant academic career, culminating in a distinguished career as the Assistant Collector of Kamalapura, begins on the day of the car festival when he is given half a rupee by Amrita Raya. As the novel describes, ‘Bhaskara went straight to the bookshop run by Christian priests and bought the Standard I English language textbook, along with a slate and a few pieces of chalk for writing’ (p. 70).