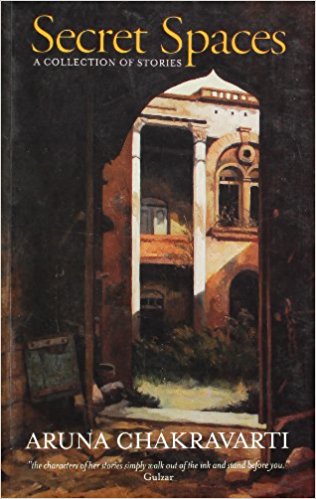

In an age where big novels dazzle with their grand historical sweep and verbal gymnastics, Aruna Chakravarti’s Secret Spaces, a remarkable collection of short stories, delights with its delicacy and understatement. Having established her skill as an acclaimed translator and a writer of long fiction, Charkravarti surprises the reader by venturing into the tight narrative space of the short story form. Her choice of form is in sync with the subjects that she deals with in her stories—the lives of ordinary women—experiences that are not part of lore or history.

It is easy to monumentalize marginality or display voyeuristic interest about ‘secrets’ that comprise so much of middle class women’s lives. Charkravarti steers clear of both these tendencies by recreating through richly textured details and oblique narratorial perspectives the half-illumined experiences of supposedly unremarkable people, mainly women, and exposes their hidden struggles, tragedies and heroism.

Most of the stories in the collection are narrated through the point of view of characters who are not the main protagonists, but are linked with the latter either as distant acquaintances or close confidantes. This narrative strategy enables the writer to enter the lives of ‘others’ from the outside and yet have an intimacy of association with them. The ‘secrets’ that are exposed then are shared secrets, and the reader too is drawn into the stories as an accomplice, an ally. ‘Princess Poulomi’ is about this rich, beautiful, spoilt young girl and her steady degeneration into poverty and finally madness. Her tale is narrated from the perspective of her one-time friend who is initially curious about the bizarre trajectory of Poulomi’s life but is ultimately unable to sustain her friendship. Here, the reader is implicated in the narrator’s guilt of having betrayed a friend who has fallen from her class. In the ‘Crooked House’ the reader shares Mala’s weakness at shrinking away from the malaise that consumes her old childhood acquaintance Chitri and her lot, who she finds years later living in utter destitution. It is not the protagonists who are judged for their moral and physical degradation—but the judgment is actually directed at the narrator and ordinary reader for being participants in a world where prejudice, class, comfort often override empathy and friendship.