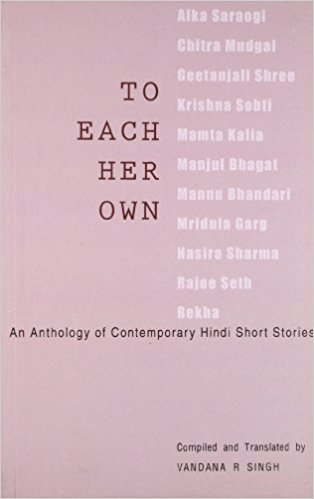

Ever since the translation of indigenous literature, mainly into English, was initiated almost a decade ago, it has triggered off reams of publications, and gradually evolved into a specific genre. Obviously, this process has been a tremendous success as publishing houses of renown have made forays into this sphere, though often glossing over prominent credits to the key player, i.e. the translator. The National Book Trust deserves credit for this well packaged, composite book on Hindi translations which acknowledges the vital cog in this whole process i.e., the compiler and translator on the cover. The translation upsurge has spawned a subtle cultural renaissance by bridging the schism between the rural/urban readership and by facilitating a convergence among various regional microcosms in the country as a wealth of literary talent unravels in English. At any rate, translations have largely been the handiwork of anglophiles, since the process of translation is not merely an elementary linguistic exercise but requires a bilingual expertise and dexterity; to capture the flavour of the colloquialisms of the terrain and the cul-tural nuances or mores imbued. This precisely defines Vandana Singh’s translatory skills as she crafts, synergizes and sieves the essence of the piece while retaining its original flavour.

December 2006, volume 30, No 12