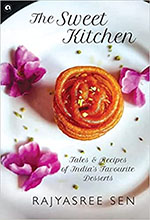

The book under review is a sweet interaction between the past and the present. The book takes the reader through the cultural and historical on sweets popular in various parts of India. The diversity of sweets in their varied shapes and textures together prepare each chapter with a historical base topped with its present understanding and existence and then generously sprinkled with the recipe towards the conclusion of the chapter.

While reading the book it felt that one was inside a sweet shop where every shelf with trays lined in perfect symmetry tells the tale from origin to modern day twists in the chosen sweet. Let us first take the tray of Sandesh, a quintessentially Bengali sweet influenced by the early Portuguese settlers in Bengal and their fondness for cottage cheese. The chhana curdled from milk is mentioned as an accidental discovery and after being flavoured with date palm jaggery, these roundrels have never looked back and continued their journey—popular till date in their new avatars of baked and blueberry flavours. The celebrated sweetmeat makers (Moiras) wove the caste-fragmented social fabric with sweet stitches of mishtis. Makha Sandesh continues to give dollops of happiness while the Sankh (conch shell) Sandesh announces happiness for all.

Moving forward is the large steel trough filled with Rosogolla. This chapter is an interesting essay on the rosogolla complete with information on the GI status battle between Banglar Rosogolla and Odia Rosogolla. The mythological interpretation of the sacrilege called ‘chhana katano’ (making cottage cheese by cutting milk with lemon/acidic substance) may find its reflection in the Rath Yatra ritual of Bachinaka as part of Niladri Bije ceremony where khirmohana is thrown away out of all other items lined up for the bhog prasad. Rosogolla Day coinciding with November 14 is a cheerful news for children and of great happiness for Nobin Chandra Das and Haradhan Moira. Rosogolla today stands at the helm of food diplomacy and this accidental sweet discovery is now available in myriad flavours and textures, some ripe with nolen gur (date palm jaggery).

Next on the shelf is Christmas Cake. Monkey cap and Christmas cake bring in December in Calcutta as the author rightly shares: the baking of this rum-soaked fruit cake is in itself a classic example of the melting pot involving the baker to the client and the celebration of Burra Din (Christmas) in Calcutta. The chapter takes us to New Market where Nahoum’s and Sons founded in 1902 resembles an archive of Jewish cultural institutions in the city. Portuguese influences with Kabuli contributions of candied seasonal fruits and that whiff of fresh baked Christmas cakes fill the localities of Calcutta from Kanchan Bakery to Flury’s.

Next to the shelf of cakes is the Kheer counter. The ubiquitous kheer/payesh/payasam is the sweet rice pudding in varied consistency which is the most humble and ready to prepare dessert in Indian homes across States. It appears naturally in homely celebrations—whether it is payesh (thickened milk with rice and jaggery added at times), or the Sheherwali version of kheer (an interesting combination of combining milk with sour raw mango). While the payasam popular in South India has milk, coconut milk, rice, pulses, jaggery and bananas. There is also the sevaiyan prepared during Eid celebrations and the coloured versions of kheer made with black rice in Manipur and red rice payasam. The recipe shared by the author at the end of this chapter makes the humble payesh/payasam/kheer appear in a tabular chart with its three common ingredients of rice, milk and sugar and an equally simple recipe for spreading happiness at home.

The chapter on halwa warmly greets the reader next. With the budget announced a few months ago, the bureaucratic tradition of preparing halwa before the enormous exercise of budget planning and presenting takes us back to the trade routes of India through which the halwa came, and soon became an important member in the great Indian mithai family. Halwa, as the author notes, originated in Arabic lands and came to India via Persia. Prepared with wheat, semolina, carrots, chick pea, eggs and many more variants, a dollop of halwa with a generous shower of dry fruits soaked in clarified butter/ghee is a sure recipe for warmth in cold winters of north India particularly.

The trays of Barfi and Gulab Jamun are like a commoners’ corner in most sweet shops. Snowy origin to the legend of Bandhi Chhor Diwas, the tale of barfi is squarely sweet in its narration. The Persian connection to the nutritious snack for local wrestlers, the barfi has moved from just its plain versions to the richer kaju katlis and gluten-laden, wheat-rich dodha barfi. The texture of the sweet allows it to be presented in different shapes and be offered in multiple hues unfurling national pride. In the essay on Gulab Jamun, the author takes us back to the Olympic Games where the Greek poet Callimachus mentions the ancestors of gulab jamun being similar to ‘honey tokens’ which were served to the winners. The Mughal emperors introduced this sweet to the Indian palate. Since then kafila-e-luqmat has continued to grow in lighter and darker shades, from kalo jam to an ode to Lady Canning with the ledikenni, this simple round or oblong sweet happily swimming in sugar syrup has become synonymous with celebrations, be it workplace or home.

The simmering cauldron of Jalebi is often used as a landmark while navigating through narrow by-lanes in Indian cities and towns. The Indian jalebi with its Middle Eastern cousin zalabiya is present in different versions and finds earliest mention in the thirteenth century Arab cookbook Kitab al-Tabikh. Navigating through these concentric circles the reader is taken to the airy delicacy found in the streets of Old Delhi between Diwali to Holi. The dessert which is whipped up from the malai is called Daulat ki Chaat, mapping its journey through the Silk Route and sharing the story of the Kyrgyz Botai tribe in Central Asia and preparation of kumis. A dessert enjoyed alike by the Mongols and Mughals continues to bring joy till date as the moon continues to smile on this heavenly concoction while it prepares itself in cold winter nights only to be dressed with slivers of almonds and saffron with a generous drape of palm sugar.

Discussing the historical background and routes through which the sweets have travelled the Curd Culture greets the reader next. Lal Doi or mishti doi is the sweet sibling of the plain curd with its range of sourness. Thickened milk with sugar or date palm jaggery has been an element of experiment in the kitchens of dairy farmers like Gopal Chandra Ghosh or mishti makers like Kali Ghosh. This sweet version of hung curd becomes shrikhand in Gujarat and Maharashtra taking forward the importance of curd in its different flavours and consistency since the era of the Rig Veda.

Colonial influences and their amalgamations into the local cuisine and kitchen are narrated well through the ‘Goan Sweets’ and ‘Relics from the Raj’. Along with potatoes, tomatoes, custard apples and vanilla, the Portuguese most notably brought to Goa sweets like doce, serradura and bebinca. These recipes have blended into the local cuisine and kitchens of Goan households. Relics from the Raj discuss the British and French influences on culinary techniques and cuisines. For example, the Franco-American wonder called Baked Alaska, along with caramel custard, bread puddings, soufflé and trifle. Each is an example of innovation with country-made re-arrangement of ingredients for the dish to sustain Indian weather conditions.

‘Ambrosia’, the concluding essay is an offering to cultural congeniality where religious celebrations bring people together through ‘mishti’ (sweet) sharing. Each festival in India brings with it a special sweet preparation with a legacy of its unique preparation, distribution and consumption. Sankranti the harbinger of new harvest brings with it a bouquet of pithas (steamed rice delicacies); folded, round, fried or flat, these preparations are a divine combination of rice, coconut and jaggery. While the author shares the details of Bengal and Odisha, she shares her experience of having Kada Prasad in the gurudwaras. While Nokul Dana or mishri is Prasad in temples, Kada Prasad is the everyday offering in the gurudwaras. Festivals in their diverse manifestations (seviyan in Eid, modaks on Ganesh Chaturthi, mohanthal with its nutty toasted flavours, shakkarapongal and chitau pitha) from north to south and west to east bind people together through ‘sweet’ sharing.

This panorama of sweets across centuries and the gathered intercontinental influences is at times a kitchen tale, sometimes a work of reference for cook-books and culinary texts, and at other times a recipe book. The author has reached out to the reader in myriad ways like the hidden layers of the marvel called Baked Alaska. Just a simple note for the connoisseurs of sweets: bhalo thakben!

November 2023, volume 47, No 11