Displacement—within and across countries—of large numbers of people, owing to political instability or civil strife, is a fact of contemporary life. UN statistics show that nearly 70 million people, or 9% of the world’s population, are displaced at present, of which more than 25 million are considered refugees. The human suffering such displacement causes—and the heroic way some affected individuals and groups overcome it to give humanity a message of hope in the midst of such strife and pain—is often ignored. This volume offers a corrective in that regard.

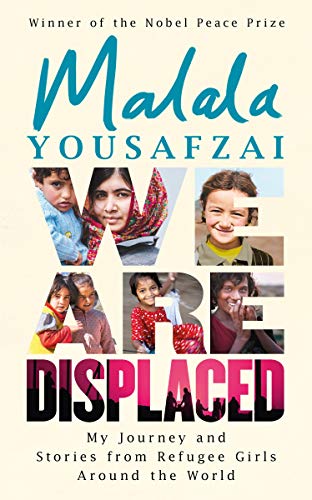

Malala Yousafzai’s personal story is well known. But in addition to the story of her own journey, she brings together in this volume the stories of nine other young women from around the world, told in their own words, to give us a more complete picture of both the suffering and its sublimation. She begins in stark, direct terms: ‘It never fails to shock me how people take peace for granted. I am grateful for it every day. Not everyone has it. Millions of men, women, and children witness wars every day. Their reality is violence, homes destroyed, innocent lives lost. And the only choice they have for safety is to leave or “choose” to be displaced. That is not much of a choice’ (Prologue, ix-x). Malala was eleven years old when she was displaced. She wrote this book, she says, ‘because it seems that too many people don’t understand that refugees are ordinary people. All that differentiates them is that they got caught in the middle of a conflict that forced them to leave their homes, their loved ones, and the only lives they have known. They risked so much along the way, and why?’ The answer is that ‘it is too often a choice between life and death.’ And ‘they chose life’, she says, as her family did a decade ago.