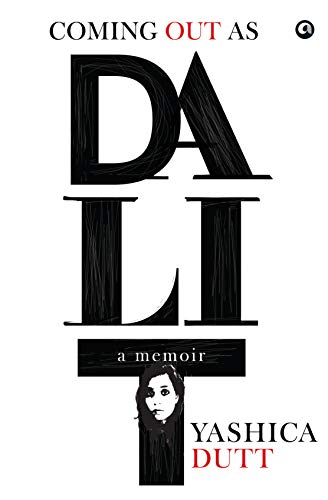

Yashica Dutt’s compellingly gritty tale offers points of identification for probably scores of third or fourth generation Dalits today, who are ‘new’ arrivals in public/professional spaces, as well as those from other marginalized, minority communities. Her memoir is a conscious exercise in reminiscing and examining lives and events, personal and communitarian, including that of her own as a student, as a journalist, and, most germane to this narrative, as a Dalit.

Dutt intersperses her story with discussions on history and politics across the span of the last century or so; her interpellation of a life against this larger canvas allows her to deftly bring out the macro- and the micro-politics of life beyond the margins, particularly in the context of north India. But the most moving parts of her account come, as far as this reviewer is concerned, in Dutt’s edgy acknowledgement of the determination of her mother to cover up the caste origins of their family.

Struggling to make ends meet, Dutt’s mother scrambled to find the means that would put her first-born—the author—into a convent school, into a hostel, into a boarding school. She began with pawning her wedding jewellery, then selling it, to finally fighting with her in-laws to sell some bit of ancestral property. She dressed her daughter in shoes and clothes and accessories that would allow her ‘to be like them’—the upper caste girls—and ‘successfully blend in’ (p. 26). Struggling with an alcoholic husband and his meagre salary in small towns, Dutt’s mother believed that ‘good schooling’ was their ‘only ticket into upper-casteness’ (p. 34). She continued to scrimp and scrounge to educate all her children—a resolution that included forays into ritual fasts, astrology and vaastu shastra (p. 50). She stitched clothes, learnt candle making, became a salesperson for Amway products, and finally worked at an NGO in the mornings while running a boutique in the evenings.