Jhalkaribai, in Brindavanlal Varma’s novel and dalit historiographical discourse, is Laxmibai’s maid-servant, the woman responsible for the Rani of Jhansi’s halo in history. Jaishree Misra’s novel, Rani, is another such metaphorical interpretation of the Mutiny, not ‘description’, as the philosopher-historian Frank Ankersmit would emphasize, but ‘proposal’, what Misra calls ‘mere interpretation’. Lakshmibai’s story is too close to our ears to carry the heft of a historical novel; so Misra, in a clever narrative tweaking, puts the story in a few lines at the beginning of the book: ‘What strange fates had conspired to bring them together; a girl who was to become queen and a young British officer destined to wrest her land away from her.’ This is a ‘love story’, Misra is keen to emphasize, between Rani Lakshmibai and Major Ralph Ellis; this, and the events described, are Misra’s artful remaking of ‘History as Literary Text’. Here history behaves like a curtain, censoring vision and deciding on the optics of hiding and revealing. The book begins with the figure of ‘a woman’ stepping out ‘of her carriage’ and coming into view; it ends with ‘the woman’ ‘disappearing from his view’.

The Prologue-Epilogue coupling, with its opposite perspectives, the first of the woman who ‘spots’ a man she knew ‘in a distant time, in another world’, and later of that man who ‘watches’ her, aware of a ‘certain familiarity’, binds the novel to a history of ‘looking’: the purdah, the clouds, the cover of the forests, the armour plates, secret tunnels, even the funeral pyre and its smoke—all these shroud the ‘gaze’, of Rani, Ralph and the reader. This is a book where characters ‘see’ too little, if at all; dreams are not seen but felt in the forehead; visions appear but only too late, in death, when chapters of seeing have closed. History in Misra’s novel is squint-eyed, deceiving in its gaze; the Mutiny is, after all, a record of the colonizer’s false sightings and the colonized’s short-sightedness.

One of the ways in which History carries out its tricks of deception in Misra’s novel is through the rhetoric of the body. Bodies are ‘prepared for the gaze of another’; in this, Nature—the ultimate trickster—is collaborator: a man’s eyebrows ‘resembles two squashed birds’, another has ‘chicken feathers for eyebrows’, marriage is ‘a chakwa bird’, Gangadhar ‘resembles a prize cockatoo’, the Rani is ‘a humming bird’, ‘a trapped bird’, ‘an irritating fly’. Zoomorphism, especially the overdependence on avian tropes in the novel (including the ‘nightingale’ and the ‘crow’ in the Rumi epigraph) and the allied hurriedness of flight, is an aid in creating illusion, of ‘showing’ something for someone.

Similar optical illusions are achieved through elaborate descriptions of food, which by virtue of its everyday aesthetic of ingestion, of short life-spans on tables and in gullets, live only half-lives in the eye. This is, after all, the Chapatti Mutiny where food is used for both, code and consumption. The most violent death in the novel, that of the chef Mohandeo—‘his decapitated head placed triumphantly atop one of his own cooking pots, a chapatti shoved into his mouth’—further blurs the divide between the literal and the metaphorical, the ultimate dissimulation.

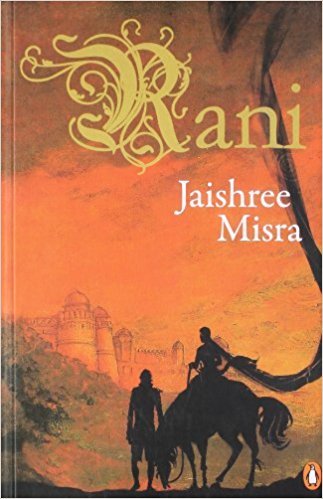

In Rani, history also comes to our gaze telegraphically, speaking in shorthand, as in the map which prefaces Misra’s text; folklorish and drawn without scale, it is an unreliable visual epigraph. So is the cover with silhouettes of a man standing beside a woman on horseback against a backdrop in orange. In both, history speaks in foggy ellipsis, as it does in the novel, confirming, if only for itself, that history repeats itself only as an imperfect reflection.

Sumana Roy teaches English at Darjeeling Government College, West Bengal. She is at present on researching in Poland and Germany.