During the 1980s, at the Department of Sociology, Delhi School of Economics, structuralism was the grand theory with which we were expected to learn about the intricacies of kinship, the contradictions of myths, and the underlying meanings of all cultural transactions. Structuralism was represented, by leading faculty members, as the theory of culture and the theory of social and cultural change. But, pouring for months over Elementary Structures of Kinship and later over The Raw and the Cooked had left me disenchanted. I thought the theory contrived, the explanations convoluted, and claims of its universal validity questionable. I became an escapee from structuralism and sought out new theories and new institutions which would enable me to understand the intertwining of political-economies with cultural forms. And, I remained distanced from bodies of literature that drew on structuralism. Reading Wilcken’s biography of Levi-Strauss reinforced many of the reservations that I had about structuralism but the book brought home to me the unusual trajectories of theories and ideas and the life of the man who was its key proponent. It provided for me a reflexive piece on the history of anthropology and the march of ideas.

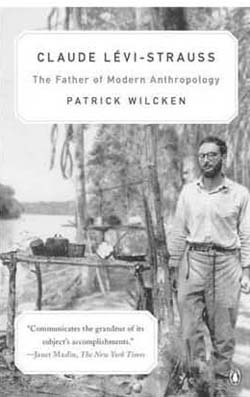

As Patrick Wilcken highlights, structuralism as formulated, elaborated on, and articulated by Claude Levi-Strauss made its remarkable impress: on anthropology as a discipline, on theories related to psycho-linguistics, art, architecture, cognitive science; and to thinkers like Jacque Lacan, Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, Pierre Clastres, and Lucien Sebag among others who themselves joined LeviStrauss in becoming intellectual icons of the world. Wilcken’s intellectual biography provides not merely details of the life of Levi-Strauss but a tracing and an assessment of structuralism as a system of thought, a bag of ideas, and an orientation that was as much a child of its times and place as its chief proponent. The book reviews the vast trove of Levi-Strauss’s works to trace the lineages of structuralism, its birth in France’s hallowed intellectual institutions, and in the then relatively unexplored vast terrains of the Mato Grosso terrains of the Amazonian basin in Brazil, a site for the then undisturbed indigenous peoples and especially for Levi-Strauss, a journey and site that defined his intellectual core.

Born into a bourgeoisie French-Jewish family in Paris, Levi-Strauss as an only child benefitted enormously from the artistic inclinations of his painter father. Influenced by Marxism, linguistics, psychoanalysis, music, and geology, the young Levi-Strauss sought out ethnological data to articulate a theory that emphasized the integral connectedness between all human societies. LeviStrauss’s life and intellectual output and reception reflected France’s own trajectory; experiencing the great depression; recovering from Nazi occupation and antisemitism of the 1930s and 1940s, the unravelling of its colonial empires in Africa and South-East Asia and the social implosion within the nation; and then the three decades of unprecedented economic growth (1975–95).