The known academic culture of India also harbours within it another unknown culture made up of provincial universities rooted in the spirit of the area. The Allahabad University, gently fading amid the dust and decay that surrounds the northern plains, is one such phenomena. Neelum Saran Gour calls her saga of the decline and fall of the Allahabad University, ‘a story teller’s history of Allahabad University, not a historian’s’. As a record of a progressive failure of India’s institutes of higher education this well researched, though on occasion somewhat sprawling, history should be interesting even for those, who (unlike the writer and this reviewer) have neither studied nor taught there.

.

The first part of the book presents a rare teleological perspective on the birth and steady growth of the Allahabad University and her sister Indian Universities in the post 1857 India. The last chapters unfurl an alarming story of how our campuses teeming with politically motivated groups of militant students and their unions set about wrecking the sytem from within and how the ruling political establishment, and its power hungry bureaucracy may have denied help to the University authorities and encouraged the students for electoral gains. Here the Allahabad University becomes a sort of a microcosm of the macrocosm. In its rise and gradual fall we come face to face with various socio-political changes that have rocked the nation and changed the face of governance. And how the Lohiyaite and JP Movements, the Mandal and Kamandal doctrines steadily created communal and caste divisions that went on to wreck the campuses, ruined the space for carrying out painstaking academic activity and research in the last four decades. This has resulted in an inevitable and gradual exodus of writers, philosophers, scientists, historians and scholars from the faculty. Even the new communication technology and renewed funding that has helped the University accsess it, have thereafter failed to open new gates to real growth and genuine intellectual activity.

As Gaur reveals India’s 19th century colonial masters had never really aimed to create totally autonomous universities for their colonies. After the Mutiny and the inglorious departure of the East India Company, the officials of the Queen’s government felt that to rule this huge land mass effectively, they would need educated native intermediaries whose loyalty to the Crown could be banked upon. Thus the Indian Universities, whose inception was announced in the historic Agra Durbar under the 1887 Act of Incorporation were created with a conscious and firm denial of the kind of autonomy the great British Universities had. The Indian universities were authorized only to teach and conduct examinations through affiliated institutions. It was the government of the day that from time to time provided the necessary policy guidelines and also the basic framework for both the syllabi and the methods for conducting examinations. Their affiliated colleges only conducted classes. This shrewd bifurcation of power was to have interesting and not always salubrious repercussions over the years.

In the post 1947 India, the bifurcation of authority continued unchallenged giving the Education Ministry a strong hold over the system. As democracy inevitably threw up its distgruntled leaders and the political climate became more and more volatile in the 1970s, this system became extremely vulnerable to the whims and political priorities of the government of the day. The basic structural weakness of our Universities funded and guided by the Babus of the Education Ministry and the ubiquitous University Grants Commission, remains to be addressed.

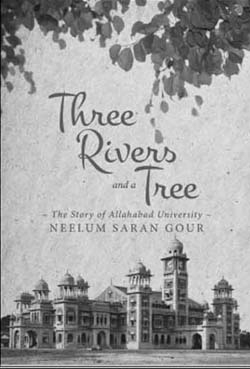

The Muir Central College of Allahabad had begun functioning in 1872 from a rented place, the Lowther Castle, for a monthly rent of Rs 250. The first chapter (The Muir Overtures) shows this college becoming the mother lode for the University in an ancient city fabled for its holy rivers and the ubiquitous Akshay Vat (a many branched banyan tree symbolic of destruction and rebirth for Hindus). After it came into being, the University adopted a many branched banyan tree as its logo, and J.G. Jennings, a principal of the Muir Central College embellished it with a Latin legend, Quot Rami Tot Arbores (As many trees as branches). Allahabad the quirky ancient city that stood at the confluence of two holy rivers, the Ganga and the Yamuna (described by Professor R.N. Deb as India’s rivers of destiny and romance and a third one Saraswati, invisible to the human eye) lend the book its bewildering title. As to why Allahabad was chosen as a site for the prestigious university when several other colleges for higher learning existed in more prosperous nearby towns like Lucknow (Canning College), Banaras (Queen’s College), Kanpur (The Christ Church College), and Bareilly, there is no academic answer but as always in India, a clear political one. During the immediate post-mutiny years when Britain was introspecting over its colonial legacies and trying to restructure ways of governing a multi-ethnic land, the locational choices were made by little known army and engineering men guided by political expediency. So while Sir Syed argued the case for establishing the University in Aligarh and Mr Mitter for Varanasi, the seat of traditional learning, the mandarins of Calcutta chose Allahabad simply because it was the new capital of the North West Provinces.

On 9th December 1873, the foundation for the Muir Central College was laid by the then Viceroy and Governor General of India, Right Honorable Thomas George Baring, Baron Northbrook of Stratton. The ceremony was attended by many princes and important citizens of the town who had donated lavish sums for a prestigious seat for higher learning in the plains of north India. Some interesting details follow (culled from the Muir College annual reports) about how several students who went on to become major celebrities (such as Sir Sunderlal and Motilal Pandit) had some time or another failed in English and Mathematics! And in 1883 Madan Mohan Malviya (the renowned freedom fighter who established the Benaras Hindu University) had managed to fail in every subject. By early 20th century Indian nationalism had made its appearance on the campus and the British were worried about the deemed seditious activities sprouting in various affiliated colleges. Question arose: how much and what sort of English education did the natives need to make them into loyal and manly citizens of the British territories? The old joke about teaching just enough so Mukherji could understand what Chatterji speaks no longer sounded funny. So three Acts (of 1904 and 5 and later the Allahabad University Act of 1912) came in quick succession. They first created a separate Board for conducting High School and Intermediate exams and then reorganized territory for the University, reconstituting the Senate and the Syndicate.

The next four decades are recorded as golden years that began with Dr Ganganath Jha as the Vice Chancellor. Under him the departments of English, Hindi, Urdu and Sanskrit became hubs of multi-language creativity of a kind that is unthinkable today. Celebrated teachers like Meghnad Saha and K.S. Krishnan began attracting some of the best students from all over the northern plains. There follows a history of various hostels and lodges that housed the thousands of young students who thronged the University’s portals in search of learning. The fabled tutorials were the first casualty to this massive upsurge in numbers but the University was continually expanding adding new buildings to house new departments and Faculty. The senate hall complex was built and the marvellous library also began to take shape. It was at this point that the first Students’ Union was born. It had a grand beginning with Pt Govind Ballabh Pant laying the foundation for its building, and for the next three decades the Union building was to be the locomotive of students’ participation not only in the academic life on the campus, but also in the Freedom Movement that was rocking the town.

The portrait gallery that Gour presents in chapter 5 has its share of heroes and villains, geniuses and snobs, and of course wits, the prime among them (and for good reason) being the eminent Urdu poet Raghupati Sahay, ‘Firaq’ Gorakhpuri. His devastating wit and multilingual erudition remain stuff of legends. Till the late 70s, this cultural vitality of the campus was led by great teachers and poets of varied political ideological backgrounds. There were poets like Harivansh Rai Bachchan who went on to be a Hindi advisor to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the brilliant poet and editor of Dharmyug, Dr Dharmveer Bharati and P.C. Gupta, the venerable Marxist, the brothers Professors S.C. and R.N. Deb, Yadupati Sahay and Rajju Bhaiya (later the Chief of the RSS). By the late 80s, however, partisan politics had begun to exploit the inherent structural weaknesses of the system and the campus was fighting a losing battle against the petty and divisive caste and communal politics.

The three Ms, Mandal, Mandir and McDonald’s according to the writer, have whisked away what the University and the town of Allahabad once were, leaving behind empty shells seething with meaningless activity and a steady deconstruction of languages. Spelling and grammar have gone for a toss as a quirky new prose meshes Hindi with English creating a postmodern jargon through text messaging. As a central University today, the University is flush with central funds after years of deprivation. It is easy to restore heritage buildings, upgrade and update computers and spruce up the lawns and the gardens, but money cannot buy functionality in a State perennially grappling with corruption, shortages and communal violence. Allahabad University today has 11 constituent colleges. But the Faculty everywhere displays gaping holes with most seats reserved for teachers from the SC/ST and OBC categories, lying unfilled due to nonavailability of suitable candidates. Funds lie unutilized, and academic sessions are sapped of all energy by frequent clashes among frustrated students on and outside the campus.

This should be a riveting read for all who care not only for Allahabad and the University, but wish to understand the decline and fall of our great institutions for higher learning.

Mrinal Pande, Senior Journalist and Former Chairman of Prasar Bharti, studied at Allahabad University.