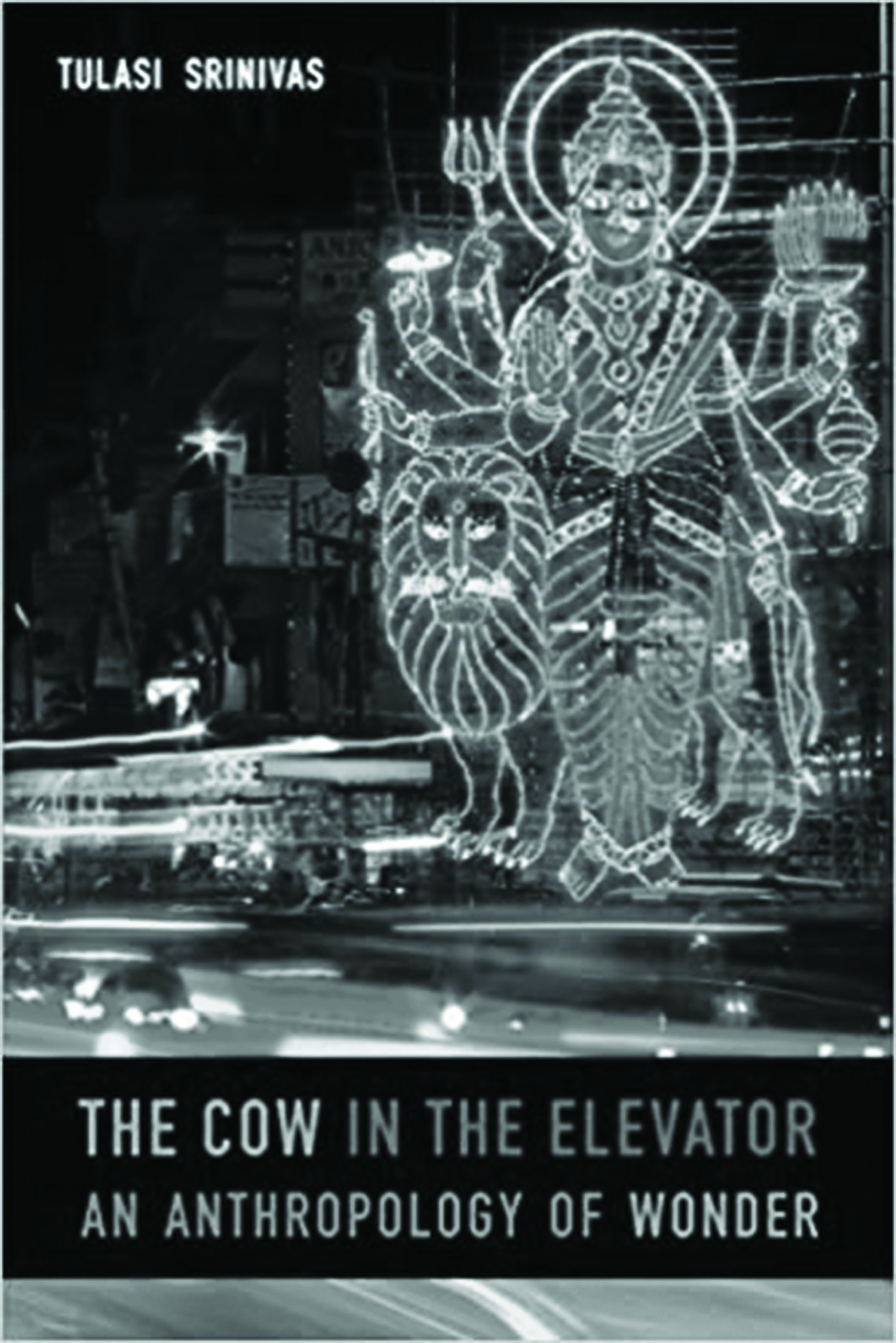

In the novel Nights at the Circus, set at the end of the 19th century in Western Europe, Angela Carter writes: ‘In a secular age an authentic miracle must purport to be a hoax in order to gain credit in the world’ (1994: 16). Carter’s novel, which follows a colourful group of characters travelling from London eventually ending up in Siberia, is defined by a tension between a new secular age of reason and doubt versus the suspension of reason and to believe in the extraordinary. It is a novel that explores wonder. But, what about situations where wonder avoids that binary between the secular and religious? Between doubt and belief? What does one do when the two polarities meld into each other in the experience of wonder? This approach is central to Tulasi Srinivas’s ethnography The Cow in the Elevator. Set in the city of Bangalore, Srinivas’s book explores the place of religion in enabling Hindus to come to terms with changes in social structure and urban space in the face of neo-liberalism.

Continue reading this review

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column]