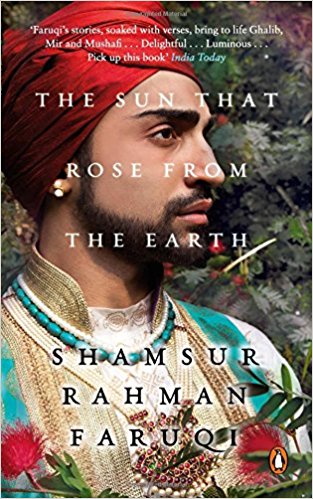

This is a collection of five long stories, rendered into English by the author himself, who first published it in Urdu in 2001 from Karachi, and, from Allahabad in 2003, with title, Savaar aur Doosray Afsanay (lit. The Rider and Other Stories). It is set in the 18th-19th centuries north India, specifically the region stretching from Delhi to Bihar. A number of major cities in this area are conjured to life in the novel in all their vivacity, hopes, despairs, accomplishments and deprivations as also literature, art, painting, bazaars, art and artisans, crafts and craftsmen, poets, critics, commentators, streets strewn with hawkers, clothes, merchants, love, romance, pottery, cutlery (though little less on food and cuisine), diseases with details of symptoms and deaths everything is brought to life in these stories. Faruqi has words and terminologies befitting the specific era, at his command, remarkably capturing the spirit of the age. One wonders if the reason Faruqi’s creative pursuits revolve around 18th-19th century north India is that he has delved deeper into the 46 volumes of Dastan-e-Amir Hamza.

October 2017, volume 41, No 10