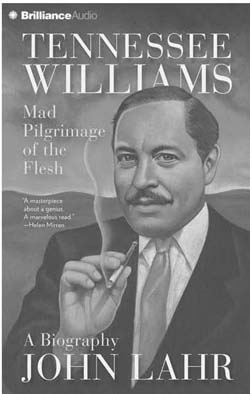

Nancy M. Tischler’s first definitive biography of Tennessee Williams appeared in 1960 when the dramatist had all but exhausted his trajectory of great writing. Tischler’s book entitled Tennessee Williams: The Rebellious Puritan was, in many ways, the first critical appreciation of the great American dramatist’s work. It wove his life—family and background—into his work and tried to offer a psycho-biographical interpretation. Another significant biography appeared in 1985—two years after the dramatist’s death. It was Donald Spoto’s well-researched biography entitled The Kindness of Strangers: The Life of Tennessee Williams. Spoto’s advantage over Tischler was of writing when Williams had long lived out his brilliant but flawed life in the sharp glare of the media, had gone down the decline path in his creativity, had suffered several fits of depression and hospitalizations before his death. Historically speaking, after 1960, Williams’s journey was all the way down into the quagmire of sadness, drugaddiction and ignominy. He could never move past, as Monte Dutton said, ‘the tortures of his life’ and as he descended into addiction and decline, he lost coherence and public appreciation. His was a grand life and Spoto captured it all and did so brilliantly. John Lahr’s recent book Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh, takes off from where the other books left off. It has the advantage of time as it has been written long after the dramatist’s death, advantage of inputs from the critical attention and researches during the centenary year (2011), and that of distance which ends all diffusion of insights.

Tennessee Williams (1911–1983) has enjoyed the reputation of a major dramatist in American theatre. Eugene O’Neill before him and Arthur Miller after, were the two other major dramatists who alongside Williams transformed American theatre and helped it individuate and grow out of British and European shadows. Among them Tennessee Williams was much more radical and explosive. Born in a puritanical family, growing up in the shadow of a bullying father, and nurtured in the repressive biblebelt of America’s South, Tennessee Williams wrote to liberate himself from the rigid cultural code. Both Henrik Ibsen and D.H. Lawrence were his well-known icons, whose work and life inspired him to revolt and cast off the straitjackets that family and society foisted on him.

When Tennessee Williams started writing, portrayals of sexual themes on stage was mostly tabooed. It is for this reason that O’Neill rarely ventured into open exploration of sexual themes. American drama did not enjoy Henrik Ibsen’s freedom to deal with sexuality as a subject. Williams however made frequent forays into this forbidden area with a powerful battery of plays beginning A Streetcar Named Desire. He brought sexuality out of the closet and gave American audiences a treat they had not seen in O’Neill or Miller.

That Tennessee Williams was in many ways obsessed with sex is the theme of the book with the self-explanatory subtitle Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh. In his childhood, in the house of the Episcopal priest where he grew up, reference to anything sexual was frowned upon as retrograde and consequently denied, rejected and slurred over in favour of socially acceptable and morally becoming noble ideas. The reference in The Glass Menagerie where Amanda returns a book Tom has borrowed from a library written by the ‘insane Mr Lawrence’, as a book not worth reading, is a case in point. Lahr interprets Williams’s early boyhood experiences at home as influencing his later life with the mother with her ‘castrating wilfulness’ and ‘monolithic Puritanism’ playing a major role in stunting his growth as a normal adult.