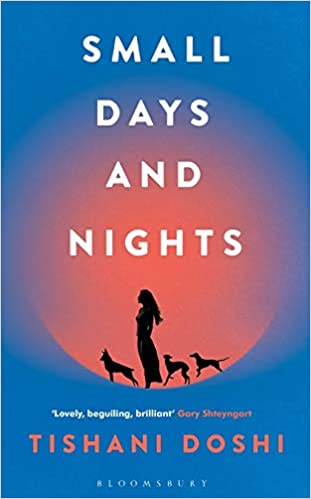

It is understandable that Tishani Doshi as a poet would prefer to write slowly. But she extends the principle of slow writing to her prose works too, speaking of its value in a note at the end of her debut novel The Pleasure Seekers (2010). This means that her publications are spaced widely, but are crafted exquisitely. Unsurprisingly, Small Days and Nights, a novel Doshi published nine years after her first, has a richness of texture and a narrative fluidity. Wannabe writers in this day and age who cannot wait to sprint their way to writing glory can in fact learn a thing or two from her. The novel is indeed a beautiful ode, at the level of style, to silence, slow time and smallness (small in the Schumacherian sense). It is the poetry of her writing—its immediacy reinforced by the continuously sustained present tense—that helps to make the melancholic and heart-breaking story of estranged marriages, parental negligence, aloneness, and of sisterly solicitude bearable and even compelling.

Small Days and Nights is a richer work of fiction than The Pleasure Seekers. The latter, with its inter-racial love story, has been taken to be a portrait of Doshi’s own parents, a Welsh mother and an Indian, in fact, Gujarati father. The second novel, however, is richer not by virtue of treading on a different imaginative territory. It impresses by its more radical working through of the root idea of inter-cultural love and the ‘in between space’ that Doshi explored in her first novel, especially with regard to the offspring of the original inter-racial adventures. Small Days and Nights is then the story of the second generation. It shows that Grace, the daughter of the inter-racial lovers, has no predefined script to follow.