Beginning with nine-year-old Keshav’s desire to go to a place that is cold, triggered by his mother’s sweating in the heat as she works, The Snow King’s Daughter translates that desire into an exploration of exile and the loss of a home. This cold place happens to be Tibet, which Keshav has seen in his atlas. Looking at the atlas and imagining all the places that he could go to is a favourite pastime. In his imagination, Keshav is a grand old man who has been to all these places and knows stories about these lands.

Tibet, because it is so high and so cold captures his imagination and that is where he would go to escape the heat. That is when his mother laughs and calls him a silly boy and tells him in her knowing grown up way that their neighbour Lobsang is from Tibet.

Keshav then has questions about how she got here without her parents, for he cannot imagine going anywhere without his mother.

Amma explains to him that Lobsang and her sister were sent to India over the mountains with a guide. With a picture of a benign Gandhi looking on from the wall, Keshav also learns that Tibet, unlike India is not independent. It is under Chinese rule. Her parents have stayed back to fight for their country.

Keshav calls out to Lobsang and invites her to his straw mat house, an honour she is aware that he does not ever bestow upon anybody. Here the children’s imagination takes a leap and Lobsang becomes the Snow King’s daughter. The powerful Snow King, when he gets angry blows fire that melts the snow, so that the mountains are easier to cross for people like Lobsang and her sister. The pause Lobsang takes here is poignant with longing—she wishes her father would come soon.

Keshav’s obsession with the atlas and his putting a cross with a red pencil on places that he liked, reminds one of Conrad’s Marlow who as a little chap would look in delight at the ‘blank spaces on earth’ where he would go to when he grew up.

It is a sensitive tale, as the blurb says, of exile and longing for home,depicted sensitively in images like Lobsang’s almost-forgotten memory of snow and how ‘when you let it stay on your hand, it makes little rivers on your fingertips’.

Rajendran exploits the childhood sense of wonder at discovering new places and the child’s ability to make leaps of imagination to weave a charming tale, which is real and credible. But it is also at a certain level a simplistic view.

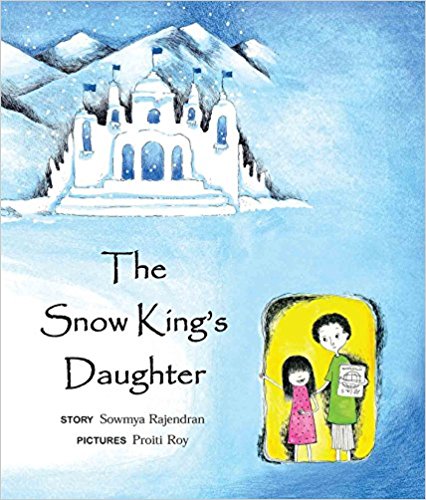

The illustrations really carry the book through—drawn with a sense of detail, adding to the emotive layer of the narrative. And adding yet another texture with the image of Lobsang and her sister juxtaposed against ‘Free Tibet’ banners sketched along with the mountains, fluttering prayer flags, an image of the Buddha, prayer wheels, monks, masks and the dome of a monastery.

While the illustrations subtly and with very real detail add a more political dimension, it is not wholly played out in the text, except for a mention of Tibet not being independent and that being the cause for Lobsang’s sojourn in India as Kehsav’s neighbour.

The explanation of the idea of independence could have been played out in a more layered manner including more of an exploration of the plural strands in India’s struggle for independence and the grittier implications of exile beyond a lyrically etched sense of the absence of a parent. The narrative makes displacement just a reference, stopping short of creating a real metaphor, which is what some of our greatest writers give us. Like Darwish’s Palestine as a metaphor for dispossession and exile.

While there is danger of dialogue that is more politically charged of degenerating into propaganda or footnotes disguised as dialogue, Rajendran’s sensibility that leads her to tell a real story infusing a lyricism with her images and a sharp sense of detail would certainly help her in overcoming that hurdle.

As the story draws to a close, Keshav puts his finger on Sri Lanka. Let us hope that Keshav and Lobsang do travel under their old straw mat house to the ‘giant teardrop beneath India’, the beautiful Sri Lanka, and learn that it is also war torn, that displacement has various shades, some more gruesome than others and all quite real. Because it is a children’s book.