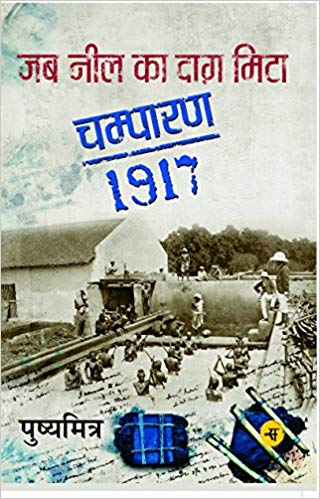

Jab Neel ka Daag Mita: Champaran 1917 recounts the processes and procedures whereby Gandhi became a Mahatma for Indians. The Champaran Satyagraha was seminal to challenging an oppressive regime of British indigo planters and restoring the rights and dignity of peasants as cultivators and human beings.

In Pushyamitra’s words, this book recounts the dilchasp dastan (interesting wonder tale) of peasant protests against British indigo planters who forced the peasants to grow indigo in their fields. The term dastan is significant as it captures the narrative structure of the book. Pushyamitra relies heavily on already available historical documents and reports on Champaran like BB Mishra’s Selected Documents on Mahatma Gandhi’s Movement in Champaran, Rajendra Prasad’s Satyagrah in Champaran, Gandhi’s autobiography, My Experiments with Truth, Rajkumar Shukla’s diary on the incidents of 1917, Razi Ahmad’s edited volume, Mahatma Gandhi ki Swadesh Wapasi ke Sau Varsh, among others. However, what sets his narrative apart from the extant reports and books on the said theme is his style which brings the history of Champaran out of the closet of history, infusing life in the events and incidents of 1917. It further analyses the varied accounts of fact and fiction, the role of Gandhi’s followers and other lesser-known people in history who invested their heart and soul in the Champaran movement and other movements preceding it. For instance, Sheikh Gulab, the protagonist of the Sathi movement (1907), Sheetal Rai, the hero of the Betiya movement (Parasa Kothi 1908), and editors/journalists of newspapers like Maheshwar Prasad (editor of Bihari) and Peer Mohammad Munis (reporter of Pratap), and peasant Rajkumar Shukla played a significant role in highlighting the oppressive terms of sharecropping like Tinkatthiya (peasants were forced to grow indigo covering at least three parts of a bheega of land), and mobilizing both the peasantry and public opinion against it. All this happened before Gandhi arrived in Champaran.

This puts Gandhi’s arrival in perspective. The readers also learn that Gandhi was not the first and only leader of the peasants. The peasants had the capacity to organize themselves against the British planters and adopt appropriate strategies to fight for their cause. For instance, if the Sathi and the Parsa kothi revolts of 1907 and 1908 were violent in nature, the presence of lawyers like Brij Kishor Prasad and motivated peasant leaders like Shukla in the Champaran movement (before Gandhi’s arrival on the scene) played a vital role in altering the method of peasant agitation. Pushyamitra writes, ‘Shukla learnt a lot from the success and failure of the 1908 movement. He prepared an alternative strategy to challenge the Britishers this time. It was his brainwave to take the Champaran matter to newspapers and courts. He would send written complaints to the government….Even as the years 1909-1917 were the worst in terms of peasant exploitation, the peasant movement did not take an overtly violent turn’ (p. 60).