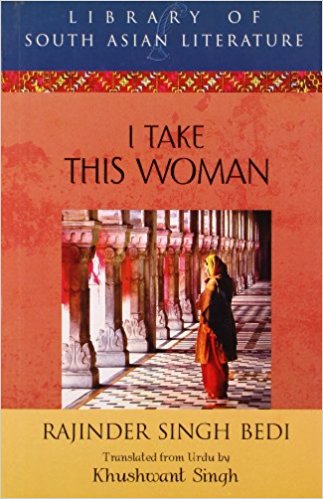

Rajinder Singh Bedi is a renowned writer, this story of his has won him the coveted Sahitya Akademi Award as well as been filmed. The translation is done by another eminent writer Khushwant Singh. He skims the nuances, homilies and flavours of Punjab’s rural landscape as well as empathizes with the traits of his community with ease. In I take this woman, the reader is transported to an unspoilt topography where the inhabitants are cocooned in folk traditions and mores essentially with the writer’s lens focusing on an overarching. patriarchal agrarian society. I would say Bedi’s narration is allegorical. Amidst the jumble of typical Punjabi life replete with minutae like howling curs, and family brawls in ‘galis’ there are grim undercurrents of malaise in the rural set up. Patriarchy is deeply ingrained in the Punjabi psyche and there is an acquiescence by the women as a survival tactic which becomes habitual from childhood; for instance, Tiriloka’s little daughter ‘Waddi’ would look after her little brother; even her play songs had reverberations about him:

We’ve come on to our rooftop I’ve a brother tall as a bamboo My brother’s wife is slender as the cypress My brother’s wife wears gold in her nose. The folk songs too sing paeans of praise for a boy: Get the cauldron on the boil—it’s a boy! The chorus replied A lovely, saucy boy—ho! A smart, spicy boy—ho! Get the cauldron on the boil—it’s a boy!.

The essence of the machismo ethos is voiced by Rano: ‘O God, do not burden even an enemy with the curse of a daughter ! She is hardly grown up when her parents throw her out to live among strangers; and if the parents-in-law don’t like her, they kick her back to her parents’ home. She’s like a ball made of cast off rags’. The skewed sex ratio reflects in the obvious son preference.

Due to social compulsions Rano has to marry her brother in law whom she has suckled at one point ‘Never, never never….’ repeated Rano. An angry shiver ran down her body. ‘Mangal is a child. I brought him up as my own son. He is at least ten if not twelve years younger than I … I cannot think of it.’ Rano runs back to her house.

The plot and the plight of the central character Rano delineates that women must sublimate their entities if social or familial pressures compel them to do so and the notion of feminity actually implied a gamut of oppressive cultural practices.

Gurpreet K. Maini is an officer on special duty with the Literary center at Punjab Bhawan, New Delhi.