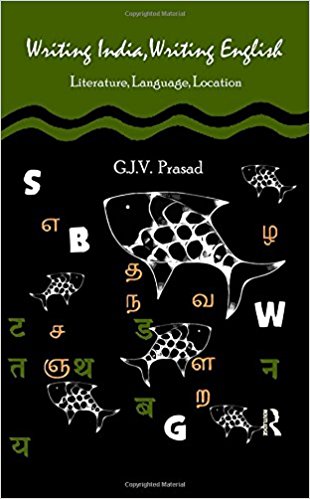

Before I begin the review of G.J.V. Prasad’s work a word on the dust jacket cover: it speaks of the multicultural, multilingual, multifarious ways in which English is read, written, and spoken in India. Hence, fish swim in a sea of words taken from Hindi, Tamil and English, the fish possibly being us who swim in the multitudinous seas that make up the many currents of English usage in India today and of yore.

Writing India, Writing English is as Prasad tells us a work that grows out of his long preoccupation with how in a country like ours, where language apparently changes every ten kos, and is accompanied by a simultaneous shift in culture, food habits, ways of living, thinking and feeling, English cannot be a fixed marker that remains changeless and inviolate. Indeed, its very changeability is what makes ‘English’ so worthy of continual critical enquiry. In the case of Prasad this enquiry becomes even more interestingly nuanced given his multiple belongings: a Tamil teacher of literatures in English in a Hindi speaking milieu.