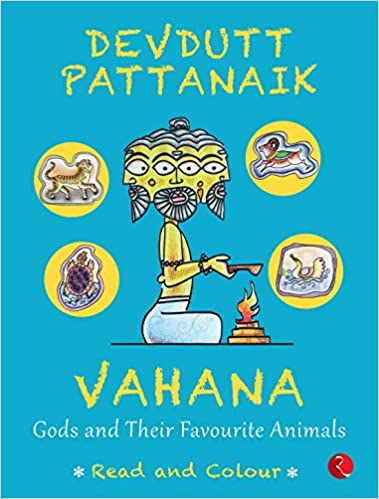

Still a child at 66, I was thrilled to get my hands on this beautiful book and sorely tempted to get the crayons on to it. Its large size made it easy to hold and the paper, including the flexible but tough cover material, most suitable for fingers, little or gnarled.

My mother, an art teacher in St. Xavier’s School, Burdwan, had in her very last year taken to such colouring books. Her eyesight was failing and her hands losing control, but the exercise of keeping her crayons within the outlines, and of matching one colour against another, kept her busy and happy, engrossed and connected. I bought her several such books available on the market, including one named Divine Vahanas: See and Paint, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai, first edition,1990.

So this book is not merely a children’s book and can have a wider, even therapeutic application. I was also happy to find its print big enough and its language simple for all ages.