While reading Intizar Husain’s Din (Day) I am reminded of Pashemaani (Regret) by Ikramullah Khan. Both the novellas have two child protagonists each, through whose experiences an idyllic life is created, against which the violence and depravity of modern life is depicted. Of course, the way the two writers deal with the afterlife of Partition is different. Ikramullah’s criticism of the atrocity and violence against marginal communities like Shia and Ahmadi is frontal and unambiguous, Husain’s response to such phenomena in his fiction is muted, couched in subtle symbolism, myths and metaphors. Both the writers recognize that violence of any kind leads to a degradation of human life and impacts the tenor of human relationships. As if as a recompense, we have touching descriptions in both the novellas of children’s attachment to the little joys of life, to the world of flora and fauna, of beautiful butterflies who act as messengers to Allah, gorgeous beetles, chameleons, neem tree blossoms that promise both normality of life and its capacity for renewal and regeneration. What the two novellas have in common also is an admirable economy of style, often austere, to depict the oppressive quotidian that threaten to overwhelm the reader by its banality, but held in control by both the writers with equal panache. I am also reminded of Abdullah Hussain’s Nasheb (Downfall by Degrees), the gem of a story that is in the same league. All of them, available in excellent English translations, depict the achievement of this sub-genre of novella in Urdu in Pakistan which, often, is overshadowed by the more prominent presence of the Urdu novel.

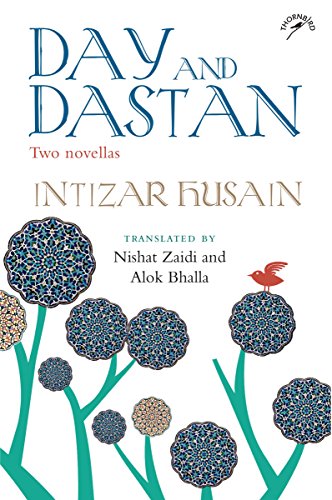

The volume under review contains two novellas–Day and Dastan–written in two radically contrasting modes, the former written in the reflective-realist mode while the latter in the mode of fantastic medieval romances. Readers of Husain approach him with a certain baggage, thinking that Partition will always be an overarching presence in whatever he wrote. In Day, the word ‘partition’ does not occur even once, and so also in Dastan, yet it is an unseen presence that frames the main plot of the novella. It is mainly the story of a lost world that cannot be reclaimed but only memorialized. It is no surprise that the most touching moments in the novel are those that involve Zamir and Tehsina, the innocence and optimism of childhood is pitted against the overarching gloom of youth and its sordid realities.

But Husain’s story is not merely one of nostalgia and the grace and charm of an old world, but also about the many little oppressions and deprivations in that world which readers and critics tend to overlook. Though they are of the same age, Tahsina’s upbringing is circumscribed by all kinds of social restrictions and taboos, and she is subjected to daily chores while Zamir had the luxury to get lost in the world of Alif Laila. He is never shown to do any chore or asked to help out. Similarly, other women in the novel seem to lack any agency and only passive receivers of the calamities thrust upon them by male choices and actions. They spend their lives in relative obscurity, spending their time in inane gossip while the men are shown to have an awareness of world events.