Bahram Modi, the Parsi merchant in Amitav Ghosh’s River of Smoke, turns to his associate in the last few pages of the novel and remarks poignantly, ‘When they make their future, do you think they will remember us… Do you think they will remember what we went through? Will they remember that it was the money we made here, the lessons we learnt and the things we saw that made it all possible?’ The urge to be remembered has been a recurring motive in history, though a privilege limited to very few. While Ghosh’s Modi meets a sad ending, the people (and histories) he was meant to represent have often been judged well by their historians. One such figure was Baron Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy— merchant, philanthropist, community leader and perhaps, an uncertain reformer.

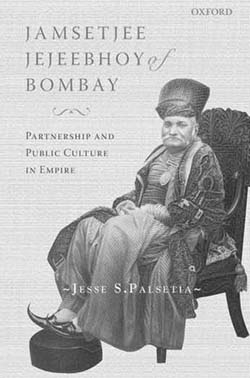

Jesse Palsetia’s Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy of Bombay: Partnership and Public Culture in Empire is an attempt to move away from the hagiographies that characterize writings on the Parsi community in India and locate Jejeebhoy within a larger constellation of actors and ideologues of nineteenth century colonialism. In the last decadeand-a-half, there has been a renewed interest in looking at the history of colonial capitalism within Indian historiography and the conscious role that many merchant communities (especially in western India) and other social elites played in this process. Such works are marked by their departure from the reductive connotations that are associated with the idea of a ‘comprador bourgeoisie’ and instead look at the ambivalence that characterized the ideological moorings of such groups. Palsetia’s work can be located within this historiographical corpus though the history of colonial capitalism is not his primary interest. Palsetia is interested instead in the ‘Non-European colonials’ role in the formation of colonial culture’, whereby the ideas from the metropole (in this case, the British) were reassessed, utilized and even, ‘retransmitted to the imperial metropolis’ (p. 4). As can be inferred, Palestia’s narrative is invested in exploring, through the lens of ‘partnership’, how an imperial culture was being conceived and deployed by actors both European and Indian. However, Palestia is acutely aware of the trouble with overburdening such a narrative with too much native agency. As he remarks, ‘Indian elites working within imperial mediums…inevitably contributed to consolidating the place of colonialism in Indian daily affairs’ (p. 114).

For Palestia, Jejeebhoy works as a perfect representative of this very idea of partnership as well as of a larger imperial culture; fraught with unequal power relations while publicly proclaiming liberal universalism. Jejeebhoy, as Palsetia shows us carefully, remained a reluctant convert. His rise as arguably the wealthiest shetia of his time was shared with his reputation as one of the most charitable and benevolent of the empire’s subjects. His acts of charity often brought Jejeebhoy’s personal religious and social beliefs in conflict with the project he had been publicly espousing, especially in instances where core Parsi beliefs seemed to be undermined. However, Jejeebhoy was astute enough to know that to be ranked as an elite recognized by the British Monarch herself, he needed to be seen committed to empire’s modernizing, universal vision of itself.

Continue reading this review