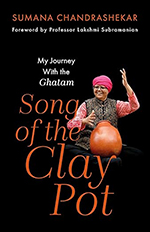

Can a pot be played as a rhythmic accompaniment to classical music? Will it find a place on the stage as an equal member with other instruments, show-casing the virtuosity and the beauty of the beat? Will it challenge and break traditional stereotypes, and finally, can a woman play the ghatam in a world dominated by men?

Many of these questions find answers in Song of the Clay Pot: My Journey with the Ghatam. For lovers of Carnatic music, this is a combination of the familiar with the unfamiliar. The book implicitly challenges the grading of instruments on the classical stage. There are vignettes of musical history. For feminists, the story of Sumana and her ghatam come together organically, where the maker, performer, and the woman sing their song of assertion in chorus, and from their distinct perspectives. The right of a woman to play the ghatam is at the heart of women’s demand for equality. Sumana’s skillful, light, matter-of-fact narrative extrapolates to see the othering as a source of inequality.

Even occasional listeners of Carnatic music may be familiar with the pot occupying the stage. After the great success of Vikku Vinayakam, the ghatam has become a part of the pantheon of percussion instruments in classical and experimental music. Sumana is part of that extraordinary narrative, of courage, determination and resilience, but her creative expression has carried these battles for diversity and inclusion of musical instruments and who plays them much further. She makes space for feminist musical expression, as she tells us that her choice ‘… to situate this memoir in the Body is not extraneous to the ghatam. Rather, it is intrinsic to it.’ Unlike most musical instruments, ‘the ghatam, is a single homogenous whole that is known simply by its parts—the belly, neck and mouth.’

There is something primeval in the sound of a drumbeat. It speaks across language, culture and continents. The beat is fundamental to human existence, whether it’s the threshing of the crop with a stick, grinding the seeds into oil, the woman at home sitting to grind the staple into flour, or walking with water on your head to the sound of your feet, and a song in your being.

The beat and the word come from the belly of the pot and the mind of the writer. As the narrative takes hold of us, the woman, the pot and its makers become ‘the Body of the earth, the Body of the maker and the Body of the player. When the three meet, there is osmosis. Each body confronts the other, shapes the other, plays the other. As they dance on the universal Potter’s Wheel, one is becoming the other.’

This is a celebratory feminist narrative as much as it is the story of a musical instrument. It is about a woman who, in playing the ghatam, is determined to oppose traditional prejudice and inequalities, which inevitably shifts to question the narrow-minded morality and interpretations of wider religious and cultural expression. Her narrative draws parallels between the instrument and the human condition, where the hierarchy of inequality is hidden in social approvals and disapprovals of women’s roles, and the intersection with religion, caste and gender across regions and schools of music.

Many of us who read the story of Sumana will be drawn in by shared experiences. As she recalls her acquaintance with the singer Rukmabai Manganiar of Barmer, Rajasthan, she kindles my memories of the husky rendering of semi-classical tones in the desert and the fearless occupation of the stage by a woman in a conventional and patriarchal world. Rukma and Sumana share the success of courage.

As she traces the story of the ghatam, we discover the history of how women became disciples, weathering storms of disapproval. Talking of the line of gurus, she says, here were men who too defied gender biases; ‘who believed that the instrument does not know whether it is a boy or a girl playing it.’ Sukanya, Sumana’s guru, becomes a performer on the stage.

This is also a story of the flowering of talent, and of persistence: the steady rise of an extraordinary woman recognized as a great player of the ghatam today. But the book makes it clear that she is more than that; she is also an engaging storyteller and a chronicler of a people’s history of music.

The drum, the pot and the various instruments of rhythm hold a special place and have played a fundamental role in the history of our lives. Drums and natural rhythms, with the human voice, were occupying musical space many millennia ago. Whatever the form of music or song, the beat has been at the centre of ceremony, at birth, life’s many celebrations and even at death. Often identified with caste and a community that has been relegated to being amongst the lowest in the social hierarchy, the drum has hidden in the shadows of acceptability.

Music is also the space where the understanding of the deep connections between social constructs and their devastating impact on a culture is presented without the obvious polarities that populate the political world. This story is of a woman and her musical pot, composing divine music. Yet, the ghatam collates and connects with all manner of oppression, from the clay of the pot and its fate because of the acquisition of land for a Kempegowda airport, the killing of many forms of traditional knowledge through the sledgehammer of land acquisition. The political divides and the deliberate divisiveness created by prejudice and power are also part of this narrative.

The ghatam transforms into a metaphor that wraps sound and gender, making Song of the Clay Pot: My Journey with the Ghatam a strong plea to change the politics of inequality. The book unequivocally and steadily critiques the musical establishment, a male and upper caste citadel, to accept change. It describes a journey wrought with contentious choices through a world where types of clay and the potter’s wheel display musical knowledge which comes from a combination of faith and instinct. The pot makers’ myths kindle people’s imagination and accommodate the expression of people without power.

Women are both part of, and a strong counter-point to a historical narrative and the myths that cement them. Through our lives we contest stereotyping, one of the most insidious ways in which we are flattened out. This book questions the woman of the two-dimensional male imagination, relegated to the world of stillness. Sumana, the player of the ghatam, as she hugs her pot, dressed in her unusual attire, challenges this prejudice.

Song of the Clay Pot–the journey of a woman and her musical pot, is essentially an ode to freedom.

Aruna Roy, a retired IAS officer turned social activist, is the founder of the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan. She has been President of the National Federation of Indian Women. Winner of the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 2000, Aruna Roy is the author of many books including The RTI Story: Power to the People (Roli Books, 2018) and The Personal Is Political: An Activist’s Memoir (HarperCollins, 2024).