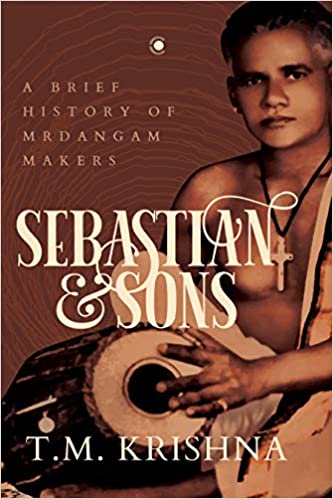

Sebastian & Sons is the intriguing title of a book on the brief history of mrdangam makers. The striking photograph of Madurai Ratnam, Sebastian’s first cousin, adorns the cover. When Krishna was asked who Sebastian was, he responded: ‘Sebastian was the oldest mrdangam maker traceable. According to me, every other mrdangam maker is the son of Sebastian, and hence, Sebastian & Sons.’

For lovers of Carnatic music, embedded in gods and temples of Hinduism, Sebastian & Sons jolts the reader to cross lines and examine music’s hidden layers of assumptions of caste and religion. It introduces us to composite, multiple feelings and skills needed before the mrdangam is born to create its music.

The release was sensational, boycotted by players, predominantly Brahmins. ‘It is he (mrdangam maker) who holds the skin with his feet and stretches it on the mrdangam. The instrument that touched his feet is kept in the singer’s puja room and revered, but the maker is not even allowed inside the same house. That is the disparity,’ said Thirumalavan, of the Viduthalai Chiruthigal Katchi (VCK). The mrdangam concert exists in a sanitized world; smells of animal hide are banished into invisibility. Leather is vital to sound.

Wow, incredible weblog structure! How lengthy have you ever been running a blog for?

you made running a blog glance easy. The overall look of your web site

is magnificent, let alone the content! You can see similar here dobry sklep