The arrival of commercial print in the 19th century, across the subcontinent allowed for the emergence of the professional writer, one who could make a living from writing alone. Where professional poets and writers had earlier subsisted on patronage from kings and nobles, the 19th century created opportunities for a writer to make a living from the market. It also, however, forced the writer to turn entrepreneur, to become an editor of a self-owned journal, to become a publisher and even set up a printing press to do the same. Bharatendu Harishchandra in Hindi, Ratan Nath Sarshar in Urdu and Bankim Chandra Chatterji in Bengali are prime examples of the writer as entrepreneur. They not only wrote books but also brought out their own periodicals and journals, and published their own books too, and subsisted largely on their writing.

These writers were creators and products of a modern literature and modern print-based literary cultures that this generated. This literary culture was modern in the sense that it was imbued with modernity, with the notion of progress, of liberty and equality and a vision of historicism. Some have seen this to be a ‘vernacular modernity,’ derivative like the anti-colonial nationalism, others have seen this as secondary to the colonial imperative of using English as a disciplinary and hegemonizing tool, and still others have seen this literature as being oppressed by the burden of its inadequacy. However, following Sudipto Kaviraj, Dubrow finds that the modernity that was the hallmark of this literary culture was expressed, at least in Urdu, and in Hindi and Bengali, through its ability and eagerness to satirize, to mock. This attitude was also reflected in its penchant for irony and parody. It is not Jennifer Dubrow’s case that satire did not exist in pre-colonial literary cultures, but that it became the hallmark of this new literary culture and was deployed to new uses and against abstractions that had come to dominate the colonial discourse.

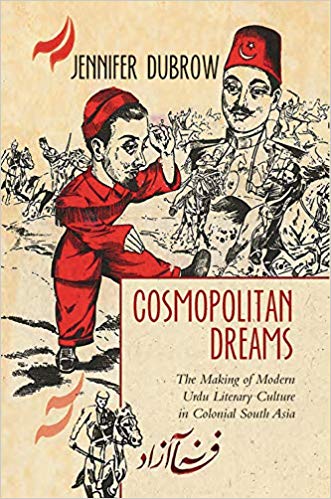

Jennifer Dubrow’s new monograph on the growth of modern Urdu literary culture breaks new ground in three aspects. Shifting focus away simply from books and poets, it highlights the importance of periodicals, journals and newspapers in the creation of a unique literary culture. Print and the commercial print revolution of the 19th century, and the new secular communities this engendered, thus becomes central to the evolution of this literary culture. She also breaks new ground by highlighting the importance of readers and consumers, manifold to a copy, in the construction of this literary culture. Finally, she defines this literary culture as the ‘Urdu cosmopolis’ which was not specific to a region, community or caste but instead describes ‘how Urdu readers and writers imagined themselves as citizens of an Urdu-speaking, transregional, yet non-national community that was global in outlook and consciously resisted national borders or religious identities.’ This new literary culture rested on the modern forms of technology such as the Railways, the Telegraph and the Postal System, all brought in by the colonial state for its instrumental purposes but put to different usages by South Asians who wanted to contest the colonial hegemony.