One of the few authentic terrors of walking unguardedly into a bookshop in these dark times is that one is almost immediately trapped by an enormous phalanx of thoroughly amiable Spiritual Books on the Inner Self which profess to alleviate all one’s worldly ills, in twelve steps or less, through a sort of spiritual enema: ills from piles to schizophrenia (and everything in between) to be fluently expunged while performing wonders, as a bonus, for one’s social, psychological and sexual life as well. With depressingly colourful covers, and even more depressingly cheerful subtitles (Every Man His Own Jesus, Around The Self In Eighty Days), they flood out of the presses like cheerily wrapped boxes of chocolate, and like chocolate they produce a temporary and illusory rapture while generating an impenitent and quite expensive addiction. One sight of these daft foot-soldiers of delirium is enough to drive any rational, red-blooded human to drink. A conspiracy theorist could argue,

persuasively, for a dark compact between the Alcoholic Beverage and the Inner Self Book industries; speaking for myself, however, every time I hear loopy words like Reiki or Art of Living or Deepak Chopra my nerves dissolve in dread and will not revive unless soaked for extended periods of time in several long, cold bottles of beer.

If Blurbs by Famous People are one sort of weapon in this fiendish artillery—and celebrity blurbs, like mid-range weapons, seem to be manufactured at an industrialized rate in our globalized era—then the shock troops of this unilateral Errorism inflicted on a guiltless and oblivious populace is Prefabricated Buddhism. There are more books on Buddhism than Buddhists in these new Dark Ages; whole forests have been felled to continue to generate these pitiless purveyors of worldly Nirvana; and every journalistic hack tricked out with barely enough information to produce an essay on Basic Buddhism is writing a book which Norman Vincent Peale would have given both arms to produce. The future of humankind looks very bleak indeed.

As if things weren’t gloomy enough already there is every sign, in recent years, of a new and pitiless weapon becoming available in the market: The Buddhist Travel Book, a projectile designed to seek out and annihilate the slightest move toward accuracy or aesthetic sense. Would you like water with your whiskey? Mark Twain was once asked by a host of his; to which he replied, famously that he didn’t because there was no point in ruining two good drinks. Defiling two perfectly good genres, however—books on Buddhism and books on travel—by concocting a revolting mélange, seems no less cardinal a sin, and one that gathers more sinners to its cause than either genre does by itself.

And they come with chummy, slangy titles, these travel books, as if the writers were all personal friends of the Buddha. Enthusiastically announcing themselves with the overfamiliarity of pushy new acquaintances—Mindful Politics, The Accidental Buddhist, Hitching Rides with the Buddha, Beyond the House of the False Lama, Rogues in Robes—they crowd the imagination as eager if imprecise lay proselytizers of Buddhism Lite. Although what they sell seems more like Buddhism Vacant.

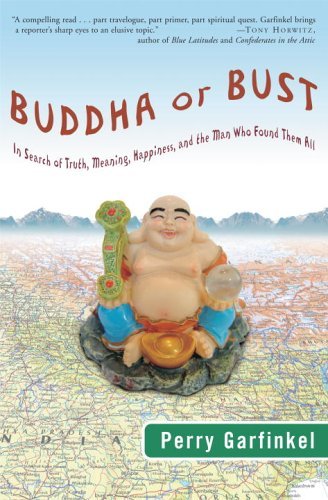

Perry Garfinkel’s Buddha or Bust is among the newest of such offerings and in its defence it ought to be said that it does possess a number of unexpected virtues. It sets itself a dual task: to rescue the author from despair, and to survey the new global phenomenon of Engaged Buddhism, a euphemism for communitarian non-governmental institutions run by Buddhists. At a bleak moment in his life Garfinkel is rescued from desolation by a plum assignment for National Geographic and a one-way transglobal ticket to visit Buddhist countries. With great good luck he lands himself with Steve McCurry, the cameraman who was catapulted to photographic immortality with his stunning shot of the Afghan girl on the cover of NG, and his Buddhist wanderings, glued together by his observations and his clearly thirsty spirit, is thoroughly sincere: there is not the slightest hint that he is searching for something in bad faith, or that his discoveries are not deeply transformative. They are, and one feels pleased for him.

But sincerity is not a literary virtue. All bad poetry is sincere, said Oscar Wilde with his usual acuity, though he could easily have extended the observation to all bad writing. Sincerity notwithstanding, this is a dreadful piece of reportage. The tone is zesty in an I’m Trying Hard To Be Zesty kind of way, and Garfinkel’s jokey asides aim at piquant but arrive at flat-as-the-skin-of-a-deflated-balloon (Example: ‘I highly doubt Eminem would know a Bodhisattva from a bodacious babe’) although he does erupt into the occasional felicitous phrase every so often. If books can be measured by the wince-factor—how often one winces at the writing—then on a scale of 1 to 10, Garfinkel’s is a hefty 22.

The virtues first, however. There are some glorious moments in the book, and all of them need mention. The first is Garfinkel’s careful and sympathetic portraits of engaged Buddhists who seem to have wrought single-handed apolitical social change across the Asian world—men such as Dr. Ariyaratne of Sri Lanka, Roongroj of Thailand, and of course Thich Na Than of Vietnam. The second is his extraordinary and quite memorable chapter on China, in which scepticism is balanced with affection, in which he falls in love, and in which he describes a Buddhist China, usually invisible, with a wholly unfamiliar geography. This is stand-alone piece which is easily carved out from the book for separate publication; and it is, refreshingly, the first travel-essay from China I have read which ignores the Great Wall utterly. (‘I didn’t have time to see the Great Wall’, Garfinkel tells us in an endearing aside.) The third is his focus on two unusual and extraordinary moments: his discovery and potted but generous history of the Shaolin temple-monastery in China, and his participation in the Holocaust meditation at Auschwitz, an authentic eye-opener, its ethics notwithstanding. There are some aspects of a book which do greater justice to themselves than a review can, and these are some of them.

But nothing is permanent. At a certain point in the book Thich Na Than, the Vietnamese master, recounts a Buddhist twist on a modern idiom for Garfinkel’s benefit: Don’t just do something, sit there, and one wishes Garfinkel had absorbed that wisdom as advice and not witticism. Whatever its virtues as a slight but interesting travel piece, the book calmly sets itself on fire every time it tries to say something sensible about Buddhism. Even the most basic thing.

Here’s a starting point for some magnificent forms of Errorism perpetrated upon our credulous sensibilities: We are introduced early on to the four noble truths, those stepping stones of Basic Buddhism. The first truth, we are told, is that there is suffering (Garfinkel gets that right). The second truth assures us that suffering is caused by ignorance of karma. Hunh? Ignorance? Karma? Where did they pop up from? In point of fact the second truth says that the cause of suffering is desire; ignorance is never mentioned in the four truths even once, except (perhaps) by extended implication. Would you trust your spiritual future to a man who gets it wrong this early in the game?

It gets worse; the book graduates from wince-worthy to flinch-guaranteed. At one particularly telling moment Garfinkel tells us with a robust certainty that Buddhist meditation is much like Freudian psychoanalysis. The Buddha and Freud? What was the man smoking? Those two systems have nothing in common except a certain claim to psychological relief, which is also shared by (say) listening to music, or watching a quietening film or, for that matter, daydreaming. Freud’s is, famously, a talking cure: speech is crucial to benefit. In Buddhist meditation, on the other hand, speech is explicitly forbidden: the effort is what one scholar has called enstasy, silent self-observation. Then, as if this is not enough damage, Garfinkel uses the Buddha to out-Descartes Cartesianism, surely a first. I shudder to recount it; you’ll have to take my word for it. Jhana, a basic Buddhist method, is translated as ‘ecstasy’ (jhana-dhyana-cha’an-zen are cognates, none of them ecstatic forms), and history is thoroughly rewritten: ‘Many, many centuries after Moguls had swept Buddhism from India…’ begins one sentence and one doesn’t know where to begin to point out the grammatical, lexical and factual mutilations in those ten words. The Bodhi tree is called ‘the most hallowed hunk of wood’ (that dreadful chumminess again); Quantum and Meditation are aligned once more in a hideous resurrection of the New Age Physics of Capra and his kin; and for all his attempts at insights, the Buddha is sanitized. Despite his visit to Auschwitz, for instance, Garfinkel nowhere mentions that the Buddha was the sole survivor of an ethnically motivated genocide which successfully exterminated all his people; or the political motivation behind several (failed) assassination attempts upon him, or his infrequent but pungent use of foul language. Just as the Christ who blasted the fig tree in Qumran in a fit of bad temper (for not growing figs) is either avoided or theologized, so too are the Buddha’s words which he unleashed at his cousin’s suggestion: ‘I would not hand over the samgha to a dog, Devadutta, how much less so to a globule of spittle such as you.’ Fighting words, those, and Devadutta responded with stout attempts to kill the man.

Bad words and genocide aside, erroneous facts and poor quips aside, mistranslations and incompletion aside, well, all those aside, there is no book left, only three pleasant episodic gems which deserve to fight for independence from the gross mass of the rest. As weapons go this is a water pistol, and its only claim to attention is as a test-case of how much of it you can read before your temper comes to a roiling boil. There are some books, as a friend of mine once said, that the author may have felt he had to write in order to ease a weighted heart, but there is no reason why we ought to feel compelled to read them. There is already too much suffering in the world. Even the Buddha (really) knew that.

Arjun Mahey teaches in the Department of English, St. Stephens College, Delhi University, Delhi.