‘It is a truth universally acknowledged,’ writes Jane Austen in the opening lines of Pride and Prejudice, ‘that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.’ The same alas cannot be said of a woman of good fortune, especially if she is a widow not a particularly old and an unattractive one at that. Traditional societies have always found it difficult to figure out ways of dealing with widows. While modern times may have seen a lessening of the old hostility and social discrimination, the position of a widow continues to be a tenuous one at best. She walks a daily tightrope between family honour and her own wishes, between playing a role that society expects of her and the one she might wish to play on her own, unscripted and unrehearsed. This tightrope becomes especially fraught if she is not too old and decrepit, that is, if the prospect of romance and a possible second marriage lurks somewhere in the background.

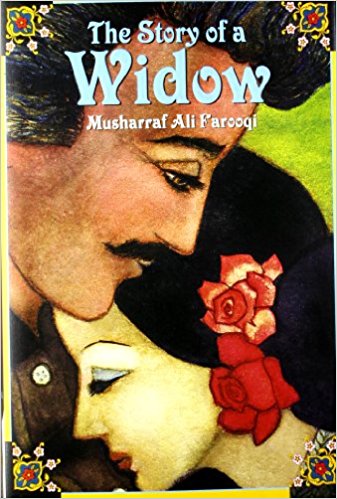

This possibility, faint and frowned upon though it is, becomes the subject of Musharraf Ali Farooqi’s slim but evocative novel. Its strength lies not in its daring to explore such a possibility. Others, after all, have written on widow remarriage, most notably Premchand. But Farooqi does so unencumbered by any moral compulsions or social obligations; he simply seizes upon this possibility and teases out a remarkably sensitive story from so slender a prospect. An Author’s Note, appended at the end of the book rather than the beginning, explains the genesis of the story, and the inspiration behind it. Farooqi writes:

The portrait that inspired this story hangs in a house in Toronto. My wife, Michelle, and I saw it when visiting an octogenarian gentleman and his third wife, whose first husband had been dead for many years; his portrait hung above her current husband’s rocking chair. She told us that when getting married she had made it clear that the portrait would stay and that her husband-to-be had happily consented. While he was telling us of his many adventures with women, the portrait surveyed the room with a magisterial air, and I wondered what kind of relationship existed between the two gentlemen: one in the chair and the other in the frame. My thoughts soon became the story of the widow and her new husband.