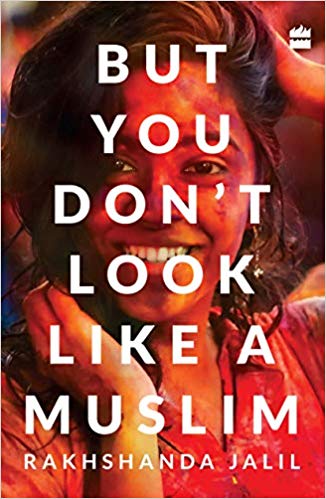

‘How is one supposed to look like one’s religion?’ With these opening lines, the author, Rakhshanda Jalil sets the premise of her book which questions the common imagination of Muslims as a community. Through various essays, Jalil stresses that all the Muslims are not cut from the same cloth. The book is divided into four broad themes of identity, culture, literature and religion containing ten essays in each chapter. The essays are written over a period of time containing her life experiences. The book cannot be categorized as a memoir, a book of anecdotes or a political commentary as it is a mix of all this and more.

In the chapter titled ‘The Politics of Identity’, Jalil gives references to all those incidences from her life where she had been ‘othered’ because of her religious identity. These may not be very stark instances of discrimination in the sense of approaching the court of law but are still important for one’s life of dignity. In the introduction itself, the author marks the perceived distinction between ‘they’ and ‘us’. All the bearded people with surma (kohl) in the eyes or skullcap on head are ‘the terrifying other’ whereas ‘us’ are those who are vegetarian and hence considered ‘nonviolent’.

The book traces instances from popular culture and media. Cinema has a power to shape people’s perceptions and ideas therefore it should abstain from stereotyping. Indian Cinema in pre and post-globalization era has manufactured a certain stereotypical image of Muslims. The only transformation in this image over the years is from paan chewing to tech savvy yet devout cold-blooded jihadists. This steady and subtle infiltration of ideas in public discourse has done more than alienate Muslims. On the same note, in one of the later essays, ‘Of Kings, Queens and Invaders’ in Part 2, Jalil highlights the mass hysteria created by recent movies, most notably by Padmaavat. Other than misogyny and the narrative of the chaste and the promiscuous, Padmaavat creates a notion of ‘native Hinduism’ and ‘foreign Islam’: the sinister, bestial, slanted kohl-lined eyed, raw meat-eating pervert versus sanskari native ruler. Following this, the author takes a strong position on the episode of the Charlie Hebdo killings. The author condemns the killing but at the same refuses to call herself ‘Je Suis Charlie’ because of the ‘irresponsible, inopportune and imbecilic’ stereotyping by the magazine ‘with strong political subtext’ (p. 29).

Dude, you should be a writer. Your article is really interesting. You should do it for a living

Great blog post, I’ve bookmarked this page and have a feeling I’ll be returning to it often.

I believe other website owners should take this internet site as an model, very clean and excellent user pleasant style and design.

cheap auto insurance quotes online… […]the time to read or visit the content or sites we have linked to below the[…]…

An fascinating discussion will probably be worth comment. I do believe that you ought to write on this topic, it might certainly be a taboo subject but normally folks are there are not enough to talk on such topics. An additional. Cheers

Comfortabl y, the post is really the sweetest on this notable topic. I match in with your conclusions and also can eagerly look forward to your upcoming updates. Simply saying thanks will certainly not just be enough, for the phenomenal lucidity in your writing. I will directly grab your rss feed to stay abreast of any kind of updates. De lightful work and also much success in your business endeavors!

I was very thankful to find this site on bing, just what I was searching for : D also saved to fav.

I really like this website! I love the content. .__________________________________ .Dayton Ohio Roofers

Affordable tours… […]the time to read or visit the content or sites we have linked to below the[…]…

This web page is really a walk-through its the internet you desired with this and didn’t know who need to. Glimpse here, and you’ll definitely discover it.

well, our bathroom sink is always made from stainless steel because they are long lasting”

Woh I like your content , bookmarked ! .

It’s difficult to acquire knowledgeable folks about this topic, but you could be seen as you know what you are speaking about! Thanks

Tremendous report! I seriously took pleasure in that going through. I’m hoping to share further of your stuff. I believe that you have superb awareness and even visual acuity. We are exceedingly empowered just for this guidance.

There are certainly a lot of details like that to take into consideration. That is a great point to bring up. I offer the thoughts above as general inspiration but clearly there are questions like the one you bring up where the most important thing will be working in honest good faith. I don?t know if best practices have emerged around things like that, but I am sure that your job is clearly identified as a fair game. Both boys and girls feel the impact of just a moment’s pleasure, for the rest of their lives.

I went over this web site and I think you have a lot of great information, saved to fav (:.

mobile devices are always great because they always come in a handy package;

Awesome post, where is the rss? I cant find it!

You have remarked very interesting points ! ps nice website .

I don’t usually comment but I gotta state thanks for the post on this great one : D.

The the very next time Someone said a blog, I hope it doesnt disappoint me as much as this place. Come on, man, Yes, it was my choice to read, but I actually thought youd have something interesting to express. All I hear is actually a few whining about something that you could fix when you werent too busy in search of attention.

You can also put a chatbox on your blog for more interactivity among readers..`*`:

Hoping to go into business venture world-wide-web Indicates revealing your products or services furthermore companies not only to ladies locally, but nevertheless , to many prospective clients in which are online in most cases. e-wallet

Simply wanna input that you have a very nice website , I enjoy the pattern it really stands out.

I just wanted to comment and say that I really enjoyed reading your blog post here. It was very informative and I also digg the way you write! Keep it up and I’ll be back to read more in the future

If we do a exercise with Hip Hop Abs program, which is properly guided for us, we would be extremely happy. Because, Hip Hop Abs is designed by a professional, and there would be a professional touch would be there. At the same time it is designed also for dancing purpose.

As far as me being a member here, I wasn’t aware that I was a member for any days, actually. When the article was published I received a username and password, so that I could participate in Comments, That would explain me stumbuling upon this post. But we’re certainly all members in the world of ideas.

I love forgathering useful info, this post has got me even more info!

I love blogging and i can say that you also love blogging.~,;..

This would be the right weblog for anyone who wants to learn about this topic. You understand a whole lot its nearly hard to argue to you (not that When i would want…HaHa). You definitely put a fresh spin on the topic thats been revealed for many years. Wonderful stuff, just wonderful!

I found your blog web site on google and check a couple of of your early posts. Proceed to maintain up the superb operate. I simply further up your RSS feed to my MSN Information Reader. Looking for forward to studying extra from you in a while!…

I always visit new blog everyday and i found your blog.;”\””`

An fascinating discussion is worth comment. I feel that you should write a lot more on this topic, it might not be a taboo subject but generally folks aren’t sufficient to speak on such topics. To the next. Cheers

F*ckin’ awesome things here. I am very glad to look your article. Thanks a lot and i’m looking ahead to touch you. Will you please drop me a mail?

The tips you provided here are very valuable. It absolutely was such an exciting surprise to get that waiting for me immediately i woke up this very day. They are often to the point and straightforward to understand. Warm regards for the clever ideas you have shared above.

I wish to get across my admiration for your kindness supporting those people who must have help with this one field. Your personal commitment to getting the message all through had become really insightful and has constantly made folks just like me to attain their desired goals. Your new useful tutorial signifies a lot a person like me and extremely more to my colleagues. Regards; from each one of us.

Some truly marvelous work on behalf of the owner of this web site, perfectly great subject material.

In the event another person bores to tears, your current hurting can be short-lived. With breast augmentation in aventura the conclusion from the event, people meet up with people that tickled the nice as well as proceed from there. Should you don’t connect with any one a person clicked by using, there is no pressure therefore you can certainly merely move household plus go to your next session. This is certainly turning out to be an extremely favorite technique for singles, and in many cases people who could model it and perhaps visit ‘as the joke’ as well as with a dare find yourself enjoying by themselves.

Cheers for this excellent. I was wondering if you were thining of writing similar posts to this one. .Keep up the great articles!

It is quite a effective point! Really wanna express gratitude for that information you have divided. Just keep on creating this form of content. I most certainly will be your faithful subscriber. Thanks again

Thanks for sharing this excellent write-up. Very interesting ideas! (as always, btw)

Hello! Good stuff, please keep us posted when you post again something like that!

I was recommended this web site by my cousin. I’m not sure whether this post is written by him as nobody else know such detailed about my trouble. You’re amazing! Thanks!

i’m fond of using vending machines because you can instantly get a drink or a snack..

An intriguing discussion is worth comment. I think that you ought to write read more about this topic, it might not often be a taboo subject but usually persons are not enough to chat on such topics. To the next. Cheers

I have read other blogs along the same topic as yours but none have really been as detailed. I really appreciate your thought you put into it. It really shows. Thanks again.

Darnit, why do you might have to make this kind of excellent points. many thanks.

Thanks so much for sharing this great info! I am looking forward to see more posts!

getting backlinks should be the first priority of any webmaster if he wants to rank well on search engines,.

But wanna say that this is invaluable , Thanks for taking your time to write this.

I really like your blogposts on here but your Rss has a handful of XML errors that you need to fix. Excellent post nevertheless!

I genuinely enjoy examining on this web site , it has got great posts .

When I originally commented I clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get four emails with the same comment. Is there any way you can remove me from that service? Thanks!

I used to be suggested this web site by my cousin. I am not positive whether or not this put up is written by him as no one else realize such detailed about my trouble. You’re amazing! Thanks!

Woah! I’m really enjoying the template/theme of this blog. It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s very difficult to get that “perfect balance” between user friendliness and appearance. I must say you have done a great job with this. In addition, the blog loads extremely quick for me on Chrome. Exceptional Blog!

I’ve been surfing on-line greater than three hours as of late, but I by no means found any interesting article like yours. It¡¦s pretty worth enough for me. In my opinion, if all website owners and bloggers made good content as you probably did, the internet can be much more useful than ever before.

Great post, you have pointed out some fantastic details , I too conceive this s a very fantastic website.

I very much like “longest current winning streak” as a tiebreaker in theory, but I think SOS issues are likely to make it tough in practice.

Read carefully the complete short article. There is certainly some definitely insightful data here. thanks. “The soul is the captain and ruler of the life of morals.” by Sallust..

I am frequently to blogging and i also genuinely appreciate your content regularly. This great article has truly peaks my interest. I am about to bookmark your web site and maintain checking for new details.

Howdy! I just want to give an enormous thumbs up for the great information you might have here on this post. I will likely be coming back to your weblog for more soon.

I really like your article. It’s evident that you have a lot knowledge on this topic. Your points are well made and relatable. Thanks for writing engaging and interesting material.

*I’d have to check with you here. Which is not something I usually do! I enjoy reading a post that will make people think. Also, thanks for allowing me to

I do not understand exactly how I ran across your blog because I had been researching information on Real Estate inWinter Springs, FL, but anyway, I have thoroughly enjoyed reading it, keep it up!