2016 got off to an inglorious start for India Pakistan relations with the attack on Pathankot’s Air Force base by terrorists allegedly affiliated to the Jaish-e-Mohammad militant group. The outfit, headquartered in Bahawalpur district, a cotton farming area in Pakistani Punjab, is one of a number of terrorist outfits operating in the region. In addition to Bahawalpur, areas like Rahim Yar Khan, Dera Gazi Khan, Chiniot and Jhang are considered fertile breeding ground for terrorist recruitment. Tashfeen Malik, one of the San Bernardino shooters, was apparently radicalized in Multan.

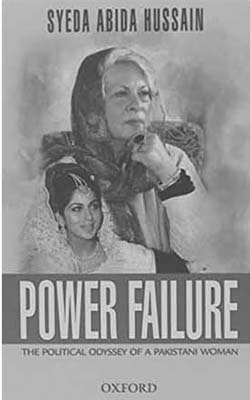

So when Power Failure, a provocatively titled political memoir by Syeda Abida Hussain, who hails from Jhang, and is one of Pakistan’s most prominent and longest serving politicians, hit the shelves last year, it certainly caused a buzz.

Close to 700 pages, Power Failure is an immensely readable account of Pakistan’s political journey since the 1960s by the ultimate insider. It provides entertaining and sometimes revealing insights into how things came to pass in present day Pakistan, chronicling events as they unfolded and dishing gossip along the way.

At first pass, Syeda Abida Hussain, affectionately known as ‘Chandi,’ would hardly seem a likely candidate for the rough and tumble of Pakistani politics, especially of the type found in chauvinistic rural Punjab. In terms of antecedents, Ms. Hussain is Pakistan’s most patrician female politician and was once its most beautiful (Nusrat Bhutto likened her to Elizabeth Taylor). To the manor born, she was the only child of a prominent Shia, Syed Abid Hussain, the youngest elected member of the 1946 All India Constituent Assembly, a thirteenth generation landowner in Jhang, and a descendant of Pir Shah Jewna, a local saint. Her mother Kishwar was the daughter of Sir Syed Maratib Ali, a very successful Lahore based industrialist. To this day, the family owns vast estates in Lahore. There was nothing in her background to suggest that she wouldn’t follow the time-honoured tradition of marrying young, marrying a fellow feudal, having children, settling into domesticity and enjoying the attendant whirls of society. She did do all that, marrying her cousin Syed Fakhar Imam, with whom she has three children, but a life of domesticity wasn’t for her.

(Full Disclosure: I have known Abida Hussain and her children since 1987; we met in Islamabad, where my father was India’s Deputy High Commissioner; my mother played bridge with her mother; her children continue to be my friends.)

The book’s early chapters are riveting, capturing a bygone era in a much less radical, more stable, secure nation. So superior in its social standing was her family that, when, in 1962, at age 16, Ms. Hussain caught the eye of President Ayub Khan’s son, who wanted to marry her, her father was aghast. An usurper of power like Ayub Khan would never do as a family for his beloved Chandi, and Syed Abid was advised by the wife of the deposed Prime Minister, Malik Sir Firoz Khan Noon, to quietly send his daughter away to Europe. Two years at finishing school in Switzerland and a year in Florence studying art history thus fashioned a sophisticated cosmopolitan.