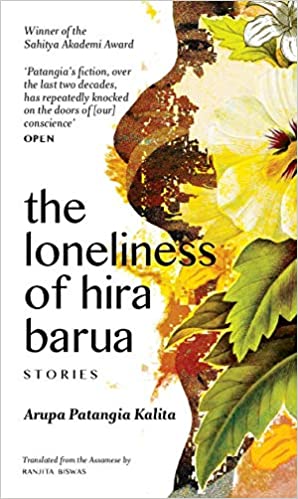

Throughout the arts, the human state of loneliness has been a theme that has been explored, analysed and taken refuge in, recurring throughout cinema, fiction and art. In Arupa Patangia Kalita’s collection of fifteen short stories, which is the English translation of her 2014 Sahitya Akademi winning text originally titled Mariam Austin Othoba Hira Barua in Assamese, the eponymous state of loneliness is the kind of loneliness that confines many of her protagonists to a restrained, almost complacent suffering. Written primarily about, but not confined to women, The Loneliness of Hira Barua: Stories explores how women navigate through the fractures of grief, pain, alienation, unfamiliarity and ailments while being cocooned up in varying stretches of isolation, often against the backdrop of militancy.

The ‘Girl With Long Hair’ is a sensitive portrayal of living under the Bodoland Movement through a young Bodo girl in a village, whose fate gets sealed in a tragic encounter when she is charged with trespassing social norms dictated by student leaders. Student politics in the state has had an invigorating and complex history, with the Assam Agitation and the Bodoland Movement launched by local student unions. The synonymity and representation of the state as a patriarchal model developed a cultural chauvinism which sought to pedestalize the Bodo woman as the upholder of the community, bringing a new shift in the power dynamics in many tribal structures, which have been sociologically exemplified for their relatively egalitarian nature. In ‘Surabhi Baruah and the Rhythm of Hooves’, set in the heyday of the Assam Agitation, the protagonist, Surabhi, is ostracized by her community for holding deviating views against the movement. Surrounded by bloodied streets and singed air, her departure from the region seems to reflect the ounce of reason and calm dissipating from the Agitation which was now curbing any opposition that arose, beating professors and killing people—a rancid sign of idealism succumbing to narrow and jingoistic chauvinism. With a judgement based on reason and rationality rather than blind emotion, Surabhi’s response echoes that of the author herself who faced a similar ordeal during the movement for voicing out against the intolerance of the Agitation.

Hello every one, here every one is sharing these kinds of familiarity, so it’s pleasant to read this webpage, and

I used to pay a visit this webpage all the time.

my site; vpn code 2024

I am not sure where you are getting your info, but good topic.

I needs to spend some time learning much more or understanding more.

Thanks for wonderful information I was looking for this info for my

mission.

my web blog … vpn special code

It’s really very complex in this busy life to listen news on TV, therefore I

only use internet for that reason, and get the most up-to-date information.

Also visit my site; vpn coupon code 2024

Why users still use to read news papers when in this technological globe all

is available on web?

Also visit my blog post vpn special coupon code 2024

Hello mates, how is everything, and what you desire to say regarding this post, in my view its in fact

awesome in favor of me.

Also visit my webpage vpn coupon code 2024