This book offers a poetic journey into the art of the Pallava dynasty, celebrating its artistic triumph in inaugurating lithic traditions in southern India. The Pallavas, as is well known, came into prominence in the late 6th century through a burst of activity recorded in inscriptions and art monuments. Both have formed the subject of intense scholarship in the field, from the early writing of G. Jouveau-Dubreuil, A.H. Longhurst, C. Minakshi, A. Rea, K.R. Srinivasan, and R. Nagaswamy to the more recent studies by M. Lockwood, Susan Huntington, Marilyn Hirsh and M. Rabe. The author has distilled much of this literature, though she mostly privileges the views of K.R. Srinivasan, to bring together a lucid account of the early phase of art activity under the Pallavas focusing on their rock cut architecture and sculpture. It is aimed at the non-specialist reader, for it culls together an array of sources used in art history and archaeology to lay bare the tools for the study of these sites.

The author has taken considerable pains to collate historical and art historical data, including epigraphic and paleographic sources, to tell her story. She also overlays her narrative with quotes from Shri Aurobindo’s writings in order to evoke the creative sprit of the production of this art and the wealth of human capital that went into its making.

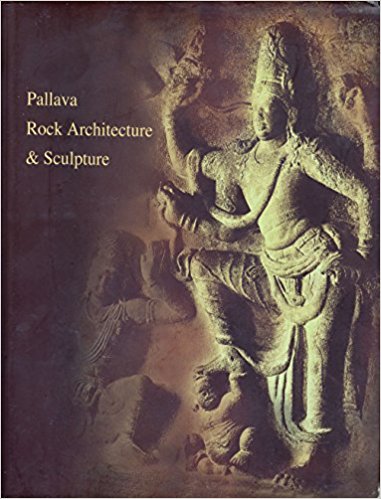

The book is a labour of love, for the author has travelled throughout the Tamil region to photograph the natural beauty of the sites, and the stunning relationship of the caves to their pristine rock surfaces. The narrative that emerges is truly evocative, for images and text work in tandem throughout, accompanied by plan drawings.

The book begins with a context to the production of stone sculpture and architecture in India. It details lithic traditions from the time of the Mauryans to that of the Ikshvakus of Andhra, acknowledged by most scholars as the immediate predecessors of Pallava sculptural art. Possibly this lengthy preamble is justified by the fact that Pallava artists did not have any traditions in stone to follow in the Tamil region, though they would have followed sculptural and architectural traditions in ephemeral materials. The view held by several scholars that the association of stone with funerary monuments, or nadukul, in this region may have led to reluctance to work in this material is also cited.

The history of the Pallava dynasty is described in great detail, giving an account of the dynasty that ‘broke with such vehemence, almost barbaric force, into the Buddhist and Bramhanical culture in Vijaypuri,’ dwelling on the fact that both Brahmin and Kshatriya affiliations are mentioned in copperplate inscriptions. The Kasakudi copperplate inscriptions, famed for their mythology of Pallava lineage and genealogy, are extensively quoted and photographed. Pallava art was strongly tied to the personality of its ruler patrons, who viewed themselves as heroic and creative individuals. This identity is reflected in the literary flourishes of their birudas or cognomens that are writ large across their stone and copper plate inscriptions. Apart from the more usual appellations such as Avanibhajana (earth vessal), Lakshita (the distinguished one), and Satrumalla (the queller of his foes), these also set up correspondences between kingship and divinity in what was to become an abiding feature of Indian art. Thus in the famed Lalitankura cave at Tiruchirapalli, a line from the biruda that accompanies the Shiva Gangadhara panel reads, ‘As the King has .. the form of Shiva, let this form forever spread throughout the world the faith…’. Beck takes care to photograph this inscription panel in situ to allow the reader to see its conjunction with the sculpted relief. Much of the success of this book lies in the detailed photography that recreates the richness of visual and inscriptional material in the study of Pallava art.

The author follows the fairly well accepted chronology for rock cut architecture and sculpture laid out by K.R. Srinivasan, based on the development of form and design in the caves, particularly their pillars. She follows their morphology closely, with the help of diagrams and photographs, explaining the meaning of each part and trailing the development of the lion base that was to become an identifying feature of Pallava pillars.

The book treats the patronage of Mahendravarman I, and his son Narasimha Mahamalla together with his successors in two sections, devoting thus a different section to the rock cut art at Mamallapuram. The latter is treated in much the same manner as the preceding section, with copious photographs and accompanying text. The themes and iconographies of the sculpted panels are described, but because of a surprising neglect of contemporary scholarship, Beck is not able to highlight the complexities of interpretation afforded by the wealth of figural sculpture and rock cut architecture at Mamallapuram. One searches in vain for a sense of enigma and mystery of this site that has enlivened the field of ‘Mamallapuram studies.’ The incompleteness of the rathas, the lively interplay of meaning in the large Descent of Ganga/ Arjuna’s penance relief sculpture, for instance, have afforded scholars great insights into the practice of sculptural traditions and the interplay of text and image in these. One can think of Susan Huntington’s essay on the iconographic design of the Arjun ratha, suggesting the identification of the Tamil folk deity Aiyanar Sasta as the main deity with its syncretistic Shaivite-Vaishnavite affiliation. Or of Michael Rabe’s lively reading of a prasasti inscription to interpret the theme of the relief panel as that of Arjuna’s penance. Or Samuel Parker’s wonderful essay on the ‘unfinished’ state of the rathas, taking an ethnographic perspective on the binaries of the finished and the unfinished in the practice of living sculptural traditions in the south.

The larger limitation is that this book does not advance any new critical insights, and Beck’s own point of view is singularly absent. This will be missed by the specialists in the field. For others, however, this book offers a comprehensive and readable account of the rock cut art of the Pallavas and its context. It is able to evoke a sense of the momentousness of its emergence and the creative energies that sustained its flowering. With some exceptions, it is also successful in marshalling the scholarship that has poured into the field.

Preeti Bahadur, is an art historian, New Delhi.