The accepted wisdom about Vijay Tendulkar’s plays is that they are about power and violence. Well, are they? Think of his ‘violent’ protagonists—Sakharam (in Sakharam Binder), Ramakant (Gidhade), Ghashiram (Ghashiram Kotwal), Benare’s prosecutors (Shantata! Court Chalu Ahe), Arun Athavale (Kanyadan), and others. Who, among them, is actually powerful? Sakharam bullies helpless women, but at the first sight of a woman with gumption, he becomes a whimpering puppy. Ramakant is abusive towards his wife, uncle and father, but cannot stand up to his two equals, his brother and half-brother. Ghashiram can be a tyrant only at Nana’s pleasure, once his ‘use’ is over, he is pitilessly cast aside. Benare’s prosecutors are petty, mean, vindictive, small men and women. Arun Athavale is a wife-beater from the historically powerless Dalit community.

Not one of them can be thought of as ‘powerful’. In fact, in crucial ways, they are all powerless. Tendulkar’s plays are about violence, it is true. But this violence is not the violence of the strong. It is the violence of the weak. This is the one line that runs through his cruel, pitiless, brutal oeuvre.

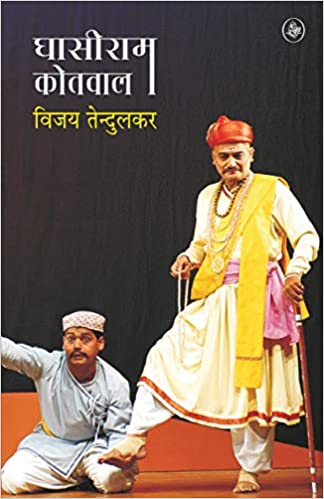

Too cruel, one has to think, too pitiless, too brutal. Which is why one is grateful for Ghashiram Kotwal. But for this play, Tendulkar’s oeuvre would be unbearable. So harsh is his language that the last thing one expects from Tendulkar is a musical. With Ghashiram, one can almost hear Tendulkar saying to the ‘theatre of roots’ wallahs, ‘Anything you can do, I can do better,’ to borrow from Annie Get Your Gun. (Though it should be mentioned that Tendulkar himself said that he did not ‘think of a form first and then look for a subject that will suit the form’. He arrived at the form, he says, through ‘a series of accidents’.)