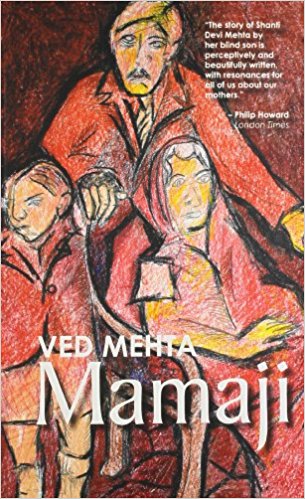

This is the third volume in a series of books about the author and his family. Daddyji, dealt with the paternal side of his ancestry while Mamaji deals with the maternal side. His own life has been portrayed in Face to Face.

March-April 1981, volume 5, No 3/4