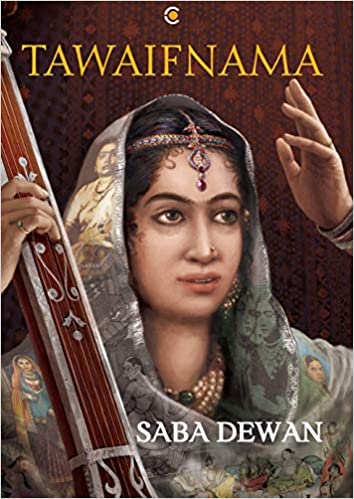

Tawaifnama is born out of Saba Dewan’s trilogy of films on ‘stigmatized’ women performers. The book is a chronicle, a history of different generations of a well-known tawaif family that had its origins in Banaras and Bhabua. The author through the stories of the family and self-histories brings forth to the reader the nuances that were wiped out by conventional histories or rewritten deliberately. It is a valuable micro-history that deserves a prominent place in the study of gender, sexuality and culture in the history of South Asia.

The author talks about her several visits to Banaras since 2002 to research and film a documentary on tawaifs, the courtesans, performers and entertainers, who almost until the mid-twentieth century played a significant role in the cultural and social life of northern India. They were, however, recast from the late nineteenth century, when they became marginalized and were ‘branded as deviant and obscene’ in Dewan’s words. Tawaifs congregated in Banaras, making it the city of the arts associated with their distinctive musical style, the bol banao thumri and its related genres such as hori, chaiti, kajari and dadra. It was with the dance form and art of the tawaifs that Kathak dance evolved. Notwithstanding their sophisticated music and dance skills, the tawaifs in a formal performance were expected to enact through facial expressions, hand gestures and dance movements each line of bandish, thumri, ghazal or any other song-type that they sang. This performance in its entirety was called mujra. In addition to being professional singers and dancers, the tawaifs functioned in multiple roles from being companions and lovers to men from local elite. Training in music and dance regardless, they were expected to acquire proficiency in literature and politics and intricacies of social etiquette and erotic simulation.